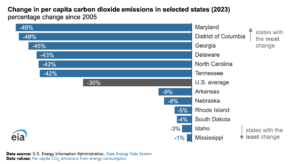

The Energy Information Administration reports that between 2005 and 2023, per-capita carbon dioxide emissions from energy consumption declined in every U.S. state. Energy-related carbon dioxide emissions fell by 20% during this period while population grew by 14%, resulting in a 30% drop in per capita emissions. The decline was mainly due to the substitution of natural gas, wind, and solar for coal in the electric generation sector. Carbon dioxide emissions continued to decline in 2024 by 0.4%, but are expected to increase in 2025 by about 1.5% due to increased consumption of fossil fuels, particularly as artificial intelligence (AI) data centers and electrification increase electricity demand. As with the trend from 2005 to 2023, per capita, carbon dioxide emissions declined more than carbon dioxide emissions in 2024 — by 1.4%.

Maryland recorded the largest decline in per-capita emissions among the states, down by 49% between 2005 and 2023. The state’s total carbon dioxide emissions dropped by 43% while its population grew by 11%. In 2005, coal and natural gas made up 56% and 4%, respectively, of the state’s electricity generation, and by 2023, those shares had shifted to 5% coal and 41% natural gas.

In 2005, the electric generation sector emitted the most carbon dioxide and continued to do so until 2016, when the transportation sector became the largest emitter of carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide emissions peaked for both the electric power and transportation sectors in 2007. Since then, carbon dioxide emissions in the electric power sector have declined faster than in the transportation sector because of the fuel-mix changes. Since 2007, the transportation fuel mix has remained relatively steady, despite increased electric vehicle sales and less petroleum transportation fuel demand since the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Climate Politics

In 2015, 195 countries gathered in France and created a climate agreement, called the Paris Agreement, that was to be a first step toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions, with each country committing to producing a plan for emission reductions. But the New York Times recently reported that the whole world, and not just the United States, has soured on climate politics.

In 2017, President Trump withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement, only to have President Biden reinstate it in 2021. President Trump again withdrew the United States from the agreement at the beginning of his second term in office. His Energy Secretary, Chris Wright, has stated, “For far too long, activists and politicians have used climate change to try and tell you how to live your life. In reality, the science and the data just don’t justify that.” To support this statement, the Department of Energy produced a report evaluating the impact of greenhouse gas emissions on the U.S. climate. Recently, he told reporters, “The Paris Agreement is silly. To agree to get to net zero 2050, it’s just a crazy, bad idea. No. 1, it’s impossible, and to try to even nudge in that direction just makes everyone poorer and makes their lives worse.”

But, as the Times indicates, it is not just the United States that is disillusioned with the politics of climate change. Few world leaders attended last year’s U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP29) in Azerbaijan, whose President praised oil and gas as “gifts from God.” Missing from the event were President Biden, Vice President Harris, China’s President Xi, and others. According to the New York Times, an official U.N. report declared that no climate progress at all had been made over the previous year. At this year’s conference, which is to take place in Brazil in November, all 195 parties to the 2015 agreement are supposed to attend with updated decarbonization plans, called Nationally Determined Contributions. In February, only 15 countries (8%) had provided input, and while more plans have been published, only one has been found compatible with the goals of the Paris Agreement. More than half represent backsliding.

The backsliding actually started earlier than last year. From 2019 to 2021, governments around the world added more than 300 climate-adaptation and mitigation policies each year. In 2023, the number dropped to under 200, and in 2024, it was around 50. In many places, existing laws have been weakened or are under scrutiny as political opponents are successful at pointing out the policies’ shortcomings. Countries are clearly agreeing with Secretary Wright — the endeavor makes no sense and is not doable.

Analysis

The significant declines in energy sector carbon dioxide emissions from 2005 to 2023 are a result of the shale revolution, which made natural gas the go-to resource for electricity generation. This change highlights the importance of private sector innovation in reducing emissions, as the profit motive provides a powerful incentive for industry to reduce resource usage and waste to lower costs. As the Cato Institute’s Marian L. Tupy argues, “The profit motive… can be added to technological improvements in production processes as a proven way of reducing fuel consumption per dollar of output and, consequently, lowering of [carbon dioxide] emissions.”

Because lowering emissions without dampening human progress requires providing energy companies with the liberty to innovate, government programs that seek to force the energy sector towards “green” energy sources by stifling investment in fossil fuels — thereby raising costs and making the electric grid less reliable — have adverse effects, while also having minimal effects on emissions reduction. As the general public begins to recognize the tangible harm climate regulations have on their well-being, they become less keen to support the regulations required for upholding agreements like the 2015 Paris Agreement.

For inquiries, please contact wrampe@ierdc.org.