Key Takeaways

Automakers have been absorbing the cost of tariffs so far, but cannot continue that practice indefinitely because they face an added cost of $2,300 per vehicle from the tariffs.

General Motors is expecting up to $5 billion in gross tariff-related costs this year, while Ford cited a tariff cost of $3 billion.

From mid-March to mid-August, the average manufacturer’s suggested retail price on new vehicles rose less than 1%, despite all foreign vehicles and auto parts being subject to tariffs of 25% and almost all imported aluminum and steel having tariffs of 50%.

Vehicles use a substantial amount of aluminum, but the United States is not a primary producer of aluminum, having produced only 1.1% of the world market in 2023.

Some question whether aluminum tariffs make economic sense.

According to Reuters, automakers have been absorbing billions in added expenses since tariffs took effect in April. However, they will not be able to continue doing so indefinitely because automakers face an added cost of $2,300 per vehicle from the tariffs. From mid-March to mid-August, the average manufacturer’s suggested retail price on new vehicles rose less than 1%, despite all foreign vehicles and auto parts being subject to tariffs of 25% and almost all imported aluminum and steel having tariffs of 50%. General Motors is expecting up to $5 billion in gross tariff-related costs this year, while Ford cited a tariff cost of $3 billion.

In some cases, automakers have increased prices on specific models, including Ford’s Mexico-produced vehicles, some Subaru models, and at luxury brands like Porsche and Aston Martin. Some tariff costs have been added to sales without direct price increases. For example, destination fees, the delivery fees to the dealership, increased 8.5% for the 2025 model year, to $1,507 — a higher amount than in the past decade. Besides absorbing the cost of tariffs, car companies can also ask suppliers or dealers to shoulder some of the cost. Automakers assembling vehicles in the United States include General Motors, Ford, Stellantis, Toyota, Honda, Hyundai, Kia, Rivian, Tesla, as well as Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen, and BMW.

As reported by Reuters, only modest price increases are expected this autumn as car dealers roll out their 2026 models. Car brands added 3.3% to their average sticker prices in August, up from last year’s increase, but in line with historical averages. Carmakers are worried about losing customers to competitors if they raise prices too quickly, as average new- and used-vehicle prices have risen about 30% after the COVID pandemic, to $49,077, due to inflation and supply chain issues.

Many vehicles purchased in the United States are assembled in Canada and Mexico and many vehicles assembled in the United States have substantial parts imported from Canada and Mexico. In July, North American automakers paid $1.389 billion in import duties related to vehicles assembled in Canada and Mexico. More than $1.1 billion in tariffs was imposed on assembled vehicles from Canada and Mexico, and another $276 million was levied on auto parts.

USMCA Agreement

Products that comply with the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA) rules of origin are not supposed to be subject to tariffs. The current USMCA has a formal review date of July 1, 2026, but, because the United States has to go through several legislated steps, it has recently started the process, which begins with a 45-day review period. President Trump has placed tariffs on Canadian and Mexican steel, aluminum, and automobiles, which will likely be part of the negotiations between the three countries. Trump is most likely looking for higher U.S. content in North American-made cars.

According to The Globe and Mail, there are three options for the USMCA: The countries can extend the treaty for another 16 years; they can start a process of annual reviews, after which the agreement will expire in 2036; or they can withdraw from it with a six-month notice.

Aluminum Vehicle Content and Tariffs

According to the North American Light Vehicle Aluminum Content and Outlook report, North American cars use a substantial amount of aluminum, and that content is expected to increase. In 2010, the average aluminum content per vehicle was at 340 pounds, and it grew by more than 100 pounds per vehicle to 459 pounds of average aluminum content per vehicle in 2020. Aluminum content is expected to grow to 556 pounds per vehicle by 2030.

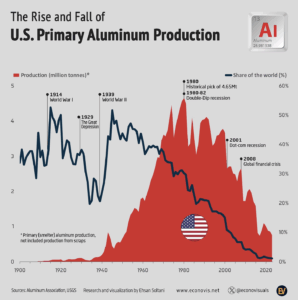

At one time, the United States was a major producer of aluminum, but that has changed. In 1913, the United States supplied approximately 35% of the world’s aluminum market, and increased its share to 53% of the world market during World War I. The U.S. world share fell during the Great Depression, but it increased again during World War II from 21% to 43% of the global market. In 1980, production peaked, and the U.S. share represented 33% of the global market. From 1998-2000, however, the U.S. share of world aluminum production fell to 16%. This downward trend has continued, resulting in the U.S. having a 1.1% share of global production in 2023. (See chart below.)

Despite this reduction in global market share, the United States is a major source of recycled aluminum — 50% of the world supply comes from one U.S. company, Novelis. Via Econovis, aluminum production encompasses primary production (extracting aluminum from its natural ore) and secondary production (recycling old and new scraps). The secondary production process involves remelting and purifying scrap aluminum from various sources, including beverage cans, car parts, building materials, and industrial scrap. Recycling aluminum is much more energy-efficient, requiring only 5% of the energy needed for primary production.

Novelis is one of the world’s largest producers of aluminum for cans of beer and soft drinks, parts for airplanes, housing construction components, and car production. The company is building a $4.1 billion plant in Bay Minette, Alabama, which is one of the largest manufacturing investments in Alabama’s history and will hire up to 1,000 workers once the plant opens. But the company is in danger of ceasing construction due to more than $40 million in monthly tariff-related costs it incurs.

Stephen Moore, visiting senior fellow at the Heritage Foundation and a co-founder of Unleash Prosperity, questions the economic sense of aluminum tariffs, which he sees killing U.S. factory jobs.

Analysis

Because of Trump’s aluminum tariffs, automakers are having difficulty continuing to offer stable prices and may be forced to raise them as their costs increase. This situation highlights the impact of tariffs: higher costs for American companies that require imported products, which could lead them to fire employees or cut wages, and higher prices for consumers looking to purchase products from these companies, leading them to delay purchases or look elsewhere. Although some industries get a small giveaway in the short term, they experience long-term productivity decreases due to insulation from competition. As Stephen Moore argues in the Wall Street Journal, “If the administration really wants a return of good blue-collar jobs, the president should immediately cancel, or at least suspend, the aluminum tariffs.”

For inquiries, please contact [email protected].