The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) recently released a study by Daniel Ahn and Michael Levi showing how a new tax on oil—which would ultimately raise pump prices by $1.20/gallon—might benefit Americans. The two main reasons were: (a) right now oil is too expensive, so taxing it would help, and (b) The revenue from a new oil tax would allow the government to spend more money, thus making the economy stronger. If the reader has not yet fallen out of his or her chair, in the rest of this blog post I’ll show that I’m not making this up.

CFR: We Need to Tax Oil Because It’s Overpriced

To establish the first claim, I can just quote from the introduction of the article itself, which says: “Economists have long argued that taxing oil consumption would be the most efficient way to address U.S. vulnerability to overpriced and unreliable oil supplies.”

It’s hard to even say much in response to this type of claim. If the problem with oil is that it’s “overpriced,” how in the world is it “efficient” to deal with that by slapping a tax on it?

As far as the “unreliability” of oil from overseas, again, it is unclear how Americans are helped by making oil more expensive. After all, if OPEC decided to cut off oil exports, the way that would manifest itself to American consumers would be a sharp rise in the price of gasoline at the pump. So to avoid this awful possibility, the CFR study proposes to…tax oil and raise prices at the pump.

A much more sensible and “efficient” solution to the problem of potential disruptions in oil imports from foreign regimes, is not to make oil artificially more expensive with a US-based taxed, but to remove US government obstacles to the development of North American supplies.

CFR: An Oil Tax Would Do the Most Good If It Were Used to Boost Government Spending

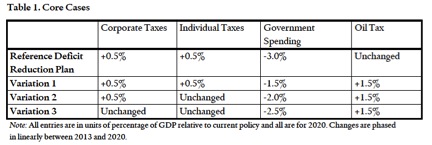

As if the introductory sentence weren’t bad enough, the meat of the article looks at various scenarios for the use of a tax on oil equal to 1.5% of GDP. Here are the three different ways that new revenue could be used, as analyzed in the study:

So in the baseline reference case, the study assumes that corporate taxes will rise by 0.5% of GDP, individual income taxes will do the same, while the government will cut its spending by 3% of GDP, for a total deficit reduction of 4% of GDP. Against this baseline case, the CFR study assumes there will be a new tax on oil, of 1.5% of GDP, which will (eventually) lead to $50/barrel tax, working out to $1.20/gallon price hikes at the pump if the tax were simply passed on.

How to use the new oil tax revenue? The CFR study looks at Variation 1, which devotes all of the new revenue to restoring half of the planned cuts in government spending. In other words, relative to the baseline case, Variation has the government impose a net tax increase on oil, so that the government can spend more.

In Variations 2 and 3, the new oil tax revenue is used to partially offset other planned tax hikes (i.e. meaning a tax cut, relative to the baseline), absorbing some of the oil revenue and leaving less for government spending.

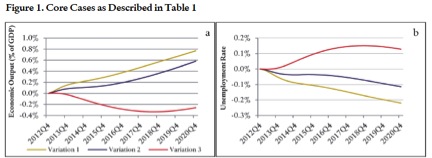

The following figures show how the study models the impact of these variations on the economy:

The above figures are quite instructive to see whether we should trust whatever model the CFR study used to generate their conclusions. Notice that Variation 1 leads (in the left graph) to a consistently growing economy, relative to the baseline case, and (on the right graph) to a consistently declining unemployment rate.

Step back and think about what that means. The CFR study is saying that if the government slapped a $50/barrel tax on oil, which works out to $1.20 per gallon of gasoline, and if it then used all of the revenue to increase government spending, then this would help the economy over an 8-year-period.

One might ask, almost in jest, “Well if a new oil tax of 1.5% of GDP is a good idea, why not make it bigger?”

Fortunately, the CFR study does just that. In the next section, they “demonstrate” that doubling the oil tax to 3% of GDP—i.e. $100/barrel of crude, or $2.40/gallon—and using all of the revenue to fuel government spending, would make the economy grow even faster, and create more jobs, than the Variation 1 from above.

Again, there’s not too much to say in response to this analysis, except that it is self-evidently absurd. Taxing energy to fuel increases in government spending is a terrible idea, if one wants to boost economic output and lower the unemployment rate. To achieve those goals, opening up federal lands to development would be much more sensible.

Conclusion

The irony is that there is nothing special about oil in the CFR study’s analysis. They don’t make an argument about climate change or other negative externalities, even though that was the context of the discussion. The actual mechanics of the underlying economic model are not spelled out, but it appears that the “results” are simply due to the alleged benefits of maintaining government spending. It is not clear why the same “results” couldn’t be generated by a 1.5% of GDP tax on coal, milk, or Slim Jims. It seems the crucial thing in the CFR study is that government spending be maintained, in order to keep the economy humming.

For people who don’t think government spending is the source of economic strength, a better policy would be to unleash entrepreneurs to develop domestic energy resources. This would reduce energy prices and make the supplies more reliable, thus mitigating the alleged problem with oil consumption. In addition, it would allow for more revenue for the federal (and other) governments, allowing them to reduce the deficit without raising other taxes.