Key Takeaways

One of the technological spinoffs from the U.S.’s prowess in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing used for oil and gas production is its potential application to geothermal energy.

Large electricity consumers such as Google have found intermittent renewable electricity in the form of wind and solar to be unreliable and requiring huge costs for batteries to back them up.

Geothermal requires vast amounts of knowledge because of its challenges of deep drilling, advanced metallurgy to withstand heat, and subsurface geological knowledge, which oil and gas companies have knowledge of.

While geothermal energy is currently more expensive than some other energy technologies, its around-the-clock status and reliability are leading to investments in pursuit of lowering costs.

While California regulators are planning to phase out hydraulic fracturing for oil production, oil and gas companies are using this technology to reach hard-to-get-to geothermal (underground heat) deposits in the earth. Chevron, BP and Devon Energy are part of a group of fossil-fuel companies investing hundreds of millions of dollars in modern geothermal startups and projects to obtain heat underground that can be used to generate a constant supply of carbon-free electricity. Because most geothermal heat is deep in the earth and difficult and expensive to produce, geothermal energy currently supplies less than 1 percent of U.S. electricity, mostly from the California’s Geysers. Technological advances in well drilling, modeling and sensor technology are expected to increase geothermal energy’s share of U.S. electricity generation, all of which have been improved through the expansion of hydraulic fracturing.

Tech companies are especially interested in carbon-free geothermal energy to power their data centers. About five years ago, companies like Google launched efforts to run their operations on renewable power 24/7, but found that wind and solar power, the preferred choices at the time, could not supply uninterrupted power as they are intermittent energy producers and are dependent on weather. Therefore, they needed to find a carbon-free and reliable source of electricity.

The Technology

Geothermal plants produce steam from underground reservoirs of hot, porous rocks saturated with water, and channel it into electricity-making turbines or pipes that heat buildings. Its adoption has been limited because drilling gets more expensive and more difficult as it goes deeper. Currently, geothermal plants mostly operate where subterranean heat is closer to the Earth’s surface–typically not more than 1 to 2 miles deep. New technologies being developed would enable deeper drilling, which would allow geothermal plants to be built in places where the Earth’s heat is farther from the surface. Tapping into the hotter material at greater depths is known as deep geothermal. The goal is to ultimately reach depths where the temperature can exceed 900 degrees Fahrenheit. According to the Energy Information Administration, “Scientists have discovered that the temperature of the earth’s inner core is about 10,800 degrees Fahrenheit (°F), which is as hot as the surface of the sun.”

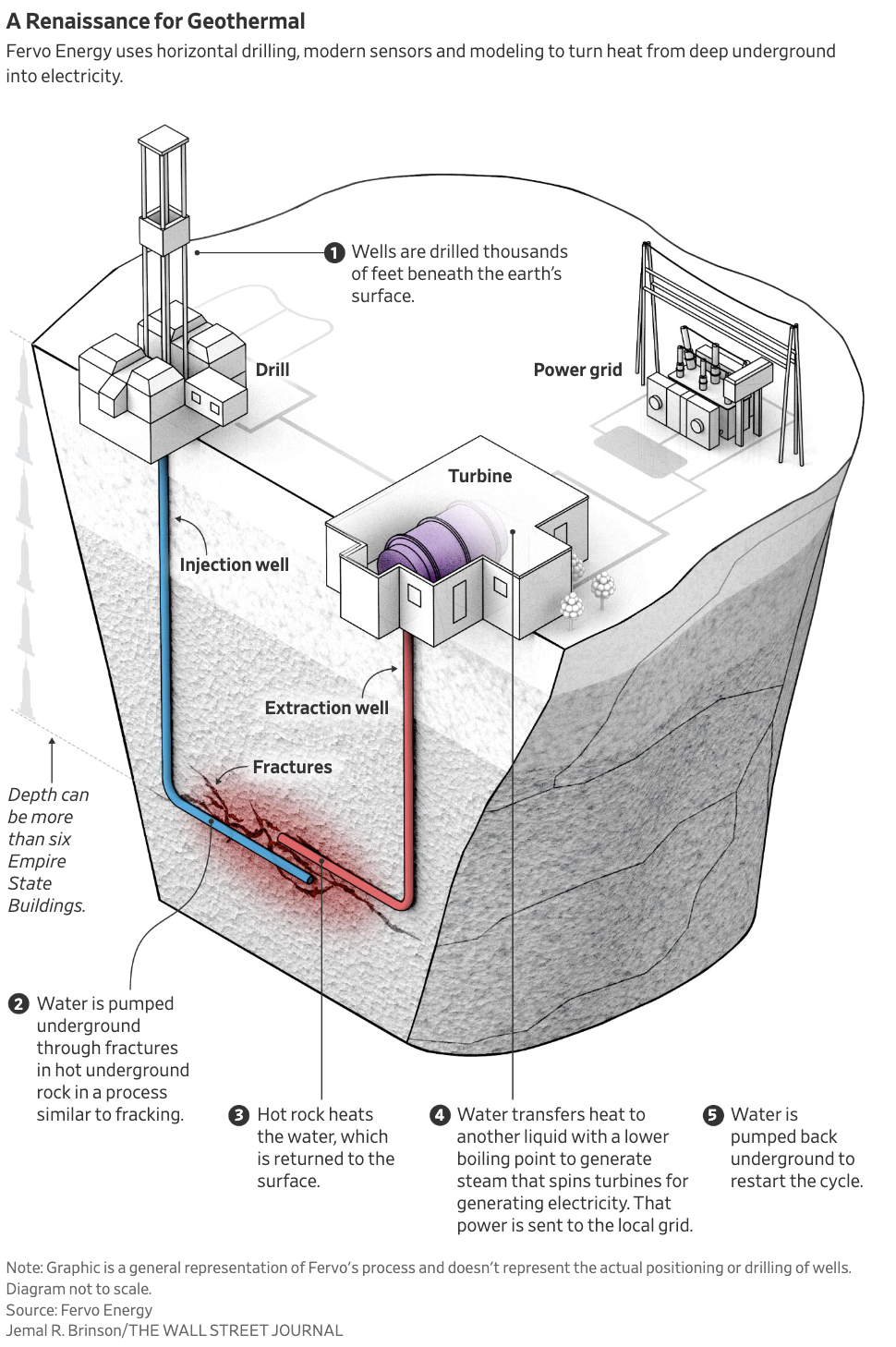

Geothermal drillers are trying to get to deep geothermal to generate electricity by using horizontal drilling and pumping water underground through fractures in rock in a process similar to fracking. After the water is heated underground, it returns to the surface, where it transfers the heat to another liquid with a lower boiling point. That generates steam, which spins turbines for generating electricity. Another offshoot is to bury a large radiator deep underground and circulate fluid through it.

Currently, geothermal power is more expensive than wind, solar and natural gas-generated electricity, forcing the industry to find ways to reduce costs. Fervo, a geothermal company, is drilling its first four horizontal wells for a project in Utah with costs almost falling by half to $4.8 million per well from $9.4 million a couple of years ago at its first commercial project in Nevada. This cost reduction tracks with the experience of oil and gas companies that pioneered the technology. Fervo plans to reach electricity costs of around $100 per megawatt hour, which is still above the cost for a dispatchable natural gas plant. Fervo recently began generating electricity from its Nevada operation to power Google data centers and other local projects.

Old oil-and-gas wells could be retrofitted to produce geothermal power, and existing wells can extract geothermal energy alongside fossil fuels, which could potentially accelerate the industry’s growth. Oil companies understand subsurface geology and have experience building infrastructure projects.

Government Support

The Energy Department recently granted $60 million to a trio of projects from companies including Chevron and Fervo, and developers can garner tax credits from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. For renewable energy projects including geothermal, through at least 2025, the Inflation Reduction Act extends the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) of 30 percent and Production Tax Credit (PTC) of $0.0275 per kilowatt hour (2023 value) to projects over 1 megawatt that meet prevailing wage & apprenticeship requirements. For systems placed in service on or after January 1, 2025, the Clean Electricity Production Tax Credit and the Clean Electricity Investment Tax Credit will replace the traditional PTC and ITC.

Electricity Demand

For the past several decades, electricity demand increased slowly along with economic and population growth, partially canceled out by efficiency gains. During the past decade, U.S. electricity sales grew by 5 percent. However, in certain states, electricity demand soared as the federal government has pushed to electrify everything from cooking to heating to personal transportation. For example, in Texas, electricity demand grew by 25 percent during that period. Tesla built a gigafactory outside of Austin, a liquefied natural gas export facility was built on the Gulf Coast and is touted as the world’s largest all-electric plant and power-hungry data centers have sprung up. Those demands are confounded by a growing population from migration into the country and between states and a high cooling demand. Texas added nearly 9.1 million residents between 2000 and 2022–more than any other state.

Data centers are one of the biggest new power consumers, and demand from them could double by 2030. Some new data centers requesting grid connections are as large as 500 megawatts. In Virginia, the state’s largest utility, Dominion Energy, connected 75 new data centers since 2019, much of it from streaming and work-from-home areas. Statewide electricity sales are up 7 percent year-to-date since then. The utility expects electric demand to grow by about 85 percent over the next 15 years. In North Dakota, oil-field electrification, bitcoin miners and new data centers have resulted in electricity sales increasing more than 58 percent in the past decade–the biggest increase in the country. North Dakota is home to the Bakken Oil Field which has improved the economy of the state after decades of stagnancy.

In coming years, computing power for artificial intelligence and wider adoption of electric vehicles will add to the demand. In addition, more manufacturing is relocating to the United States because of subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act and much cheaper natural gas. The United States is also forcing a transition from conventional power plants fueled by coal and natural gas to intermittent wind and solar power. Grid operators have warned that generating capacity is struggling to keep up with demand, and that gaps could lead to rolling blackouts particularly during hot or cold weather extremes.

Conclusion

Geothermal producers are looking to fracking to reach deep geothermal deposits as some large electric consumers are wanting a carbon free source of electricity that can operate 24/7. Currently, geothermal power makes up less than 1 percent of U.S. electricity demand because it is difficult and expensive to drill at levels needed for deep geothermal resources. Geothermal companies, however, are looking to cut those costs so that the technology can substitute for the massive amounts of solar and wind power that would be needed to meet the demand from increased electrification. The federal government is forcing sales of electric vehicles on auto companies and has introduced standards to move consumers from gas cooking and heating to electric. It is not clear when geothermal can become cost competitive or whether it can even achieve that goal. Regardless, consumers can expect higher electricity prices and blackouts when generating capacity cannot meet growing demand through forced electrification.