Key Takeaways

The 50% tariff on steel and aluminum imports has been extended to encompass hundreds of derivative products — goods now subject to tariffs based on their steel and aluminum content.

These tariffs hurt U.S. manufacturers who rely on imported materials, raising their production costs and eroding their competitiveness.

For automobiles, the tariff distorts the market, potentially favoring Japanese, South Korean, and EU auto exports, while penalizing U.S. manufacturers, who face higher costs for their inputs.

Likewise, the tariffs are disruptive to the oil and gas industry, which needs steel and aluminum for pipelines, drilling rigs, refineries, and transportation networks.

The tariffs have prompted concerns about potential cost increases and operational challenges, which are likely to exacerbate existing supply chains, leading to potential material shortages and project delays.

President Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs are now extended to 407 products that contain aluminum and steel, including car parts, plastics, and specialty chemicals. Other products that the 50% duties are applied to include fire extinguishers, machinery, furniture components, and construction materials that either contain, or are contained in, aluminum or steel. Jason Miller, a professor of supply chain management at Michigan State University, indicated that the steel and aluminum tariffs now affect at least $320 billion of imports based on 2024′s general customs value of imports, which is a 68% increase from a prior estimate of about $190 billion.

In June, President Trump announced that he was doubling tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from 25% to 50%, going into effect in March for most countries. In June, he called for a new steel and aluminum product inclusions process, which the Bureau of Industry and Security in the Commerce Department established in April. Companies had submitted requests for product inclusions in mid-May. Under Commerce’s steel and aluminum product inclusion process, there are three annual windows for the public to submit product inclusion requests. The next window will open in September and will be announced in the Federal Register.

U.S. Dependence on Imports of Steel and Aluminum

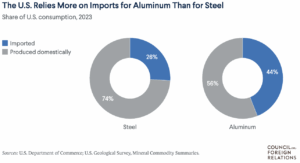

The United States depends on foreign imports for about half of its aluminum supply, and relies more heavily on imports for special aluminum products. About two-thirds of primary aluminum comes from Canada, according to the Aluminum Association, where lower energy costs make it cheaper to produce.

The United States relies less on imported steel than on imported aluminum. Domestic steel mills produce about three-quarters of American steel needs. However, U.S. automotive and energy companies rely on foreign sources for specific types of steel, such as pipes and tubes, which can withstand extreme temperatures and pressures. The United States imports about 40% of its piping and other rolled steel materials — often to drill wells — so the tax increases costs for American oil producers. Canada and Mexico are the biggest exporters of steel to the United States.

Auto and Energy Industries

The steel and aluminum tariffs affect a number of U.S. industries, including the automotive industry and the oil and gas industry. Manufacturers like Ford have reported multimillion-dollar cost surges due to the tariffs. The metals are essential for vehicle production, used in chassis, engine components, body panels, and structural reinforcements. U.S. producers have limited immediate availability to produce automotive-grade steel and aluminum, making it difficult to fully offset foreign sources with domestic ones.

American automakers, who have to pay a 50% tariff on steel and aluminum imports and their metal derivatives, see themselves as disadvantaged since the Trump administration has agreed to 15% tariffs from Japan, South Korea, and potentially the European Union. (When the EU formally introduces the necessary legislative proposal to enact tariff reductions on U.S. goods, the 15% tariff will go into effect.) Japan, for example, exports more vehicles to the United States at a 15% tariff than it does steel and aluminum at a 50% tariff. U.S. automakers are paying a steep levy on steel and aluminum they import for their vehicles, while their foreign competitors are only taxed a 15% tariff on their vehicles.

While oil and gas imports are essentially exempt from tariffs, higher steel and aluminum duties are squeezing oilfield service margins, raising costs and delaying new project timelines as the industry relies heavily on these metals for infrastructure and operations. The oil and gas industry utilizes these materials extensively in pipelines, drilling rigs, refineries, and transportation networks. The tariffs have prompted concerns about potential cost increases and operational challenges, which are likely to exacerbate existing supply chain challenges, leading to potential material shortages and delays. If domestic steel and aluminum producers cannot gear up to meet demand, companies could be forced to seek alternative suppliers, potentially at higher costs, which may also lead to delays in critical infrastructure projects. According to data from Rystad, spending on steel accounts for around 10% of upstream capital expenditures in the United States.

Analysis

The 50% tariff on steel and aluminum imports has been extended to encompass hundreds of derivative products — goods now subject to tariffs based on their steel and aluminum content. These tariffs have direct impacts on the energy industry, as these goods are needed to create pipelines, refineries, rigs, and transportation networks, in addition to their use in drilling and mining operations. Tariffs like these will not assist in making American energy great again as costs for consumers and producers will rise, on top of the disruptive effects this will have on the supply chain. Furthermore, tariffs will disproportionally harm smaller producers, stifling market competitiveness and preventing many from realizing the American dream. Tariffs are functionally no different than an increase in taxation. If the Trump administration seriously wants to increase American energy production, tariffs are not the way to go. A better approach would be focusing on decreasing regulatory and permitting barriers.

For inquiries, please contact [email protected].