Key Takeaways

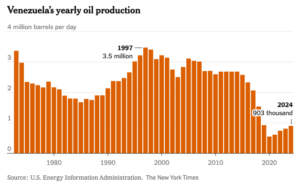

Mismanagement, corruption, and international sanctions crippled oil production in Venezuela, reducing it from 3.5 million barrels per day in the late 1990s to less than one million barrels per day in 2025.

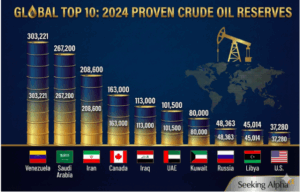

Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves of 303 billion barrels, accounting for approximately 17% of global reserves.

To fully restore Venezuela’s oil sector may take five to seven years or more than a decade by various estimates, and require U.S. oil companies to spend billions of dollars to fix the badly broken infrastructure.

Not only is the country’s oil system broken, but so too is its electrical system, which will be another challenge for companies investing in the country.

Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, but its petroleum industry, which was once very productive, has been reduced to a fraction of its former capacity due to mismanagement, underinvestment due to failed government policies, and international sanctions. Rebuilding Venezuela’s oil output from 900,000 barrels per day — less than 1% of global oil supply — to its former productivity will be a challenge and take years, billions of dollars, and political stability.

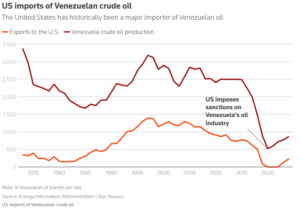

U.S. Imports of Venezuelan Oil

Venezuelan crude once flowed heavily into the United States, peaking at 1.4 million barrels a day in 1997, when the shipments accounted for nearly half of the country’s oil production, according to the Energy Information Administration. That trade eroded steadily over the following two decades, falling to about 506,000 barrels a day by 2018. After Washington imposed sanctions on Venezuela’s oil industry in 2019 in response to President Nicolás Maduro’s disputed re-election, U.S. purchases dropped to negligible levels.

As explained by Reuters, to compensate, American refiners, particularly those along the Gulf and West coasts, turned to heavy crude from Canada and Mexico. Many of those facilities were built decades ago to process dense, high-sulfur oil and are poorly suited to handle the lighter, sweeter crude produced in large volumes from U.S. shale fields. As a result, much of the domestic light oil is exported, while refineries continue to rely on foreign heavy grades to operate efficiently.

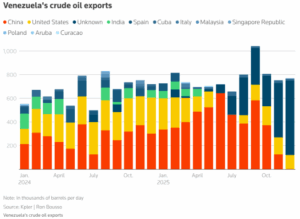

China accounted for more than half of Venezuela’s oil exports of 768,000 barrels per day last year as it became the main importer of Venezuelan oil after President Trump imposed sanctions on the country’s energy industry in 2019. Recently, China’s imports of Venezuelan oil have declined as the United States increased enforcement of oil sanctions against the Maduro regime by seizing tankers.

Venezuela’s Oil Reserves Are Extensive

Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves of 303 billion barrels, accounting for approximately 17% of global reserves, which are concentrated in the Orinoco belt region. Via EnergyNow, operations in the Orinoco Belt require advanced extraction technologies like steam injection and diluents for transport. These are technologies that U.S. companies like Chevron and ExxonMobil are known to excel in. At current prices around $57 per barrel, the potential gross value would total $17.3 trillion. Even at half that value, or about $8.7 trillion, Venezuela’s GDP would be higher than the GDP of every nation except the United States and China.

U.S. oil companies helped discover and develop Venezuela’s oil beginning in the 1920s, with Venezuela becoming the world’s second-largest producer by the 1930s. Western companies, including Chevron, Exxon Mobil, and Shell, were forced to retreat after Venezuela nationalized the industry first in the 1970s and again under Hugo Chavez in the 2000s. According to Reuters, Venezuela’s production consequently shrank from a peak of 3.7 million barrels per day in 1970 to a low of 665,000 barrels per day in 2021 before slightly recovering in 2024. The Wall Street Journal reports that, after ConocoPhillips and Exxon Mobil pulled out of Venezuela in 2007 when Chávez nationalized their assets, Conoco sued the Venezuelan government for more than $20 billion, and Exxon sued for $12 billion. The companies were awarded only fractions of their losses in protracted arbitration proceedings.

According to the Wall Street Journal, for these companies to return and invest billions in the country’s oil industry, a broad economic stabilization plan is needed to attract the financing to rebuild infrastructure and rusted oil-field installations. Local laws also need to be modified to allow private energy firms to operate without state overreach. And the government has to restructure some $160 billion in debt and settle pending arbitration cases with foreign companies, including Exxon, ConocoPhillips, and Chevron.

To fully restore Venezuela’s oil sector is estimated to take five to seven years by one estimate and by at least a decade by another, and requires U.S. oil companies to “spend billions of dollars” to fix the “badly broken infrastructure.” According to the New York Times, this includes repairing looted pipes, abandoned rigs, and a mismanaged, corrupt industry. Despite an estimated 300 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, Venezuela’s output has plummeted to about 900,000 barrels a day from about 3.5 million barrels a day in 1997. About one-third of it is produced by Chevron, exporting around 150,000 barrels per day to the U.S. Gulf Coast.

As reported by Reuters, assuming political, legal, and financial hurdles are resolved, developing new oil and gas projects would still take years. Venezuelan oil production could increase by up to 200,000 barrels per day in the first year, according to Rapidan Energy’s forecasts, and double to two million barrels per day within a decade under its most optimistic scenario.

Venezuela’s Electric Grid Will Also Be a Challenge

According to Grid Brief, Venezuela once had about 36 gigawatts of installed generation capacity. By the late 2010s, only about 10 to 12 gigawatts of capacity were available for reliable service.

Hydropower once accounted for the majority of the nation’s electricity, generating 65 to 80% in some years. The Guri Dam complex on the Caroní River in Bolívar state has a nameplate capacity of about 10,235 megawatts spread across more than 30 turbine-generator units of various sizes. Other hydro plants include the Caruachi Dam with about 2,160 megawatts and the Macagua complex with 3,168 megawatts across a couple of dozen units. When these units were affected by droughts in the mid-2010s, the country turned to thermal units to back up the hydropower. These plants include Termozulia, with about 1,590 megawatts of combined gas turbines near Maracaibo, Cardón Genevapca at 315 megawatts, and clusters of smaller units in places like Barinas, El Furrial, and Guarenas.

In the early 2010s, emergency programs purchased additional gas turbines and modular units, often under hastily negotiated contracts, to add 3,000 to 4,000 megawatts of capacity. However, many of the thermal plants were never properly integrated into the grid, lacked consistent natural gas or diesel supply, or were unfinished. Combined-cycle units were half-built, and imported wind turbines located on the Paraguaná peninsula produced almost no megawatts. By 2019, the thermal fleet’s effective contribution had collapsed, leaving hydro to carry nearly all of what little power remained.

Transmission and distribution losses rose into the mid-to-high 20% range, resulting in a quarter or more of every megawatt produced disappearing in transit due to aging lines, overheated transformers, poor maintenance, and outdated protection systems. Since 2019, the country has experienced thousands of outages each year. In western states like Zulia and the Andes, extended rationing of up to eight hours of cuts per day is normal.

Analysis

With Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro removed, a window of opportunity exists for Venezuela to become a prosperous, oil-producing country. However, any optimism should be tempered by the knowledge that achieving this outcome will require substantial political and economic reform. The lack of stable economic and social institutions, resulting in political repression and industry nationalization under Maduro and his predecessor, Hugo Chavez, caused Venezuela to reach its current level of poverty and low oil production. It would take substantial American involvement to alter these institutions. Furthermore, low crude oil prices, poor infrastructure, and still-existing political risk mean that oil companies won’t be rushing to increase production in Venezuela anytime soon.

Another important consideration is how U.S. action in Venezuela will affect U.S.-China relations. As Allen Brooks writes for Master Resource, “The decision to allow Venezuela to sell oil to China ensures that the nation will retain its commercial relationships, which are essential for ongoing international business activity. At the same time, it is a signal to China that the U.S. will enforce the Monroe Doctrine policies, removing the Americas as a focal point for increased Chinese involvement, which has involved significant investment in mines, ports, and other South American industries. The move also puts China on notice that its Venezuelan oil flows could be shut off instantly over unfriendly actions towards the U.S., changing the energy landscape for China.”

For inquiries, please contact [email protected].