While the fuel costs associated with electric vehicles may be cheaper than for gasoline vehicles in some places, that is not expected to be the case in California, where electricity prices are among the highest in the nation. Residential electricity prices in California in December 2021 averaged 23.22 cents per kilowatt hour, compared to 13.75 cents per kilowatt hour for the nation, or almost 70 percent higher. In 2021, Governor Gavin Newsom signed an executive order banning new gasoline vehicles by 2035 and President Joe Biden issued a nationwide goal of having electric vehicles account for half of total car sales by 2030. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg has repeatedly told Americans to buy electric vehicles to avoid the fluctuating costs of gasoline. But, according to a May 2021 industry report, it is cheaper to fuel a conventional internal combustion engine vehicle than it is to charge an electric vehicle, at least in one California service area. California is a leader in generating electricity from renewable energy, particularly wind and solar power, which has pushed up its electricity prices. The state has goals to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030 and reach carbon-free electricity by 2045.

Customers of Southern California Edison (SCE), Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) and San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&E)—the state’s three largest utility companies, which provide more than 65 percent of California residents with power — paid 33 cents, 30 cents and 38 cents per kilowatt hour, respectively, in March for electricity. By 2030, those prices are expected to increase 20 to 50 percent, depending on the utility company. Electric bills are projected to increase as utilities address wildfire risk from their power lines, add electric vehicle charging stations and invest in massive storage facilities intermittent wind and solar power require. According to San Diego Gas and Electric, the costs to address wildfire risks and electric vehicle charging stations are about 40 percent of the bill and include the costs for putting power lines underground and adding microgrids to keep critical resources powered during extreme weather conditions. Ratepayers ultimately pay for those added costs.

In the May 2021 industry report, the California Public Utilities Commission Public Advocates Office said that it was cheaper to fuel an internal combustion engine vehicle than to charge an electric vehicle in the San Diego Gas & Electric service area, where electricity prices are the highest. According to the analysis, that could also be the case in areas served by Pacific Gas & Electric and Southern California Edison by the end of this decade. The report’s calculations were based on the cost of gasoline early last year, when California prices averaged about $3.27 per gallon. Gasoline prices could again be that low if President Biden would remove his anti-oil policies, which are keeping oil and gas companies from investing in new projects.

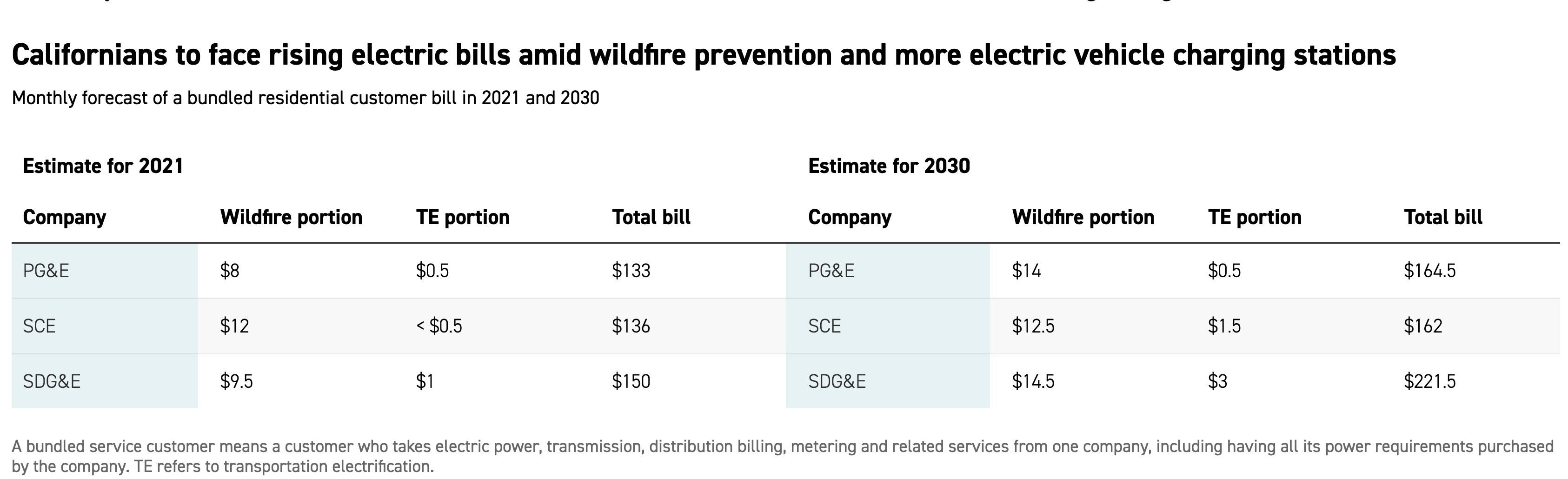

One of the biggest costs driving up electric bills is the tab for preventing wildfires. According to the report, wildfire costs add between $8 and $12 a month to the average residential bill, depending on the utility and is expected to increase to as high as $14.50 per month in 2030. The San Diego utility spent several billion dollars on system upgrades after wildfires in October 2007. Those costs typically show up several years after a fire, when the infrastructure is built. All three major utilities in California have spent billions of dollars on wildfire prevention in recent years. All of these utilities also offer various electric vehicle charging options as part of their push for electrification of the vehicle fleet. For example, San Diego Gas & Electric has an overnight rate of 10 cents per kilowatt hour plus a $16-per-month fee.

The report also identified state policies that raise electricity costs. At least 17 state mandates raise the price of power, including legislative measures that increase the share of electricity that come from renewable power sources and energy efficiency programs. In addition to wildfire costs, higher natural gas prices and growth in the share of people who get help paying their bills also raise the cost of electric bills to consumers. Programs to help low-income ratepayers are funded by other customers in California.

Also in California, net metering programs that benefit customers with rooftop solar arrays push fixed costs onto traditional customers. Net energy metering gives homeowners credits for sending their excess renewable power to the grid, allowing them to sell wholesale electricity at a much higher retail rate to utilities, who pass those costs onto consumers. According to the utilities, that cost transfer is $3.4 billion per year and increasing as more homes add rooftop solar. Solar customers get a 20-year agreement through the net energy metering program when they install rooftop panels. Customers who add solar panels get paid for electricity they send to the grid at the retail rate. They do not pay for transmission and distribution expenses that other customers have to pay.

Conclusion

California knows it has to make changes in order for its electrification program to move forward. Discussions on various changes have been taking place, including changing the net metering program to pay wholesale prices for the excess rooftop solar energy, implementing forest programs (e.g., prescribed burns and thinning and cleaning overgrown areas) to cut back on wild fires using state funds, having state funds pay for electricity for low-income ratepayers, and rate reform. Instead of charging customers for how much electricity they use with infrastructure costs included, customers would pay a fixed monthly price for a utility’s fixed costs, plus their actual generation costs for electricity used. Whether any of these changes will get California to its goals is yet to be determined. But, one thing that this California situation shows is that following in California’s path as the Biden administration is doing, is not a fruitful and sustainable future. As the above shows, it could lead to drivers paying more for electric vehicle transportation fuel than internal combustion fuels.