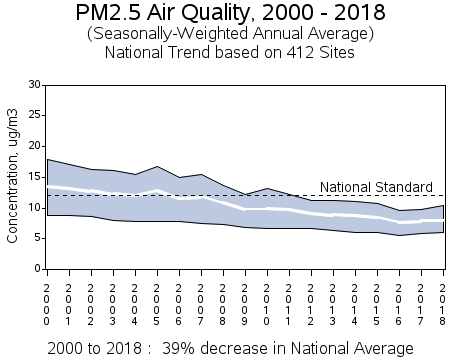

According to the EPA’s air-quality monitors, levels of particulate matter — known as PM 2.5 — have not been lower during the lockdowns caused by the coronavirus pandemic and have, in fact, been higher than the median level of the last five years. Consisting of particles smaller than 2.5 microns, PM 2.5 includes natural sources such as smoke or sea salt, as well as human-caused pollution from combustion. This result was opposite what was expected because the number of vehicles driven was far less during the lockdowns. This result indicates that, in most places, human-caused pollution is small relative to natural sources. The pandemic has shown that a significant reduction in the human contribution makes only a small difference to PM 2.5 levels, which were already under the national standard.

Another pollutant, ozone, barely decreased in some cities due to the coronavirus lockdown compared with levels over the past five years, despite traffic reductions of over 40 percent. Ground-level ozone occurs when the chemicals emitted by vehicles, factories and other sources react with sunlight and heat. In the vast majority of places, ozone pollution decreased by 15 percent or less.

It is assumed by environmentalists and indoctrinated in Americans that less driving equals cleaner air. This is a premise of the Green New Deal that expects internal combustion engine vehicles to be replaced by electric vehicles, fueled by electricity generated by politically correct renewable technologies. That premise results in more environmental regulation and more costly energy that hurt American pocketbooks.

Nitrogen Dioxide Used as an Indicator of PM 2.5 and Ozone levels

Americans are conditioned with pictures of Chinese and Indian cities where cleaner air has resulted from less driving. But the results in those areas are not applicable to the United States. Articles that cite these data focus not on particulate matter, but on nitrogen dioxide (NO2)—a pollutant associated with driving. NO2 is a concern primarily because it is a precursor to particulate matter and ozone.

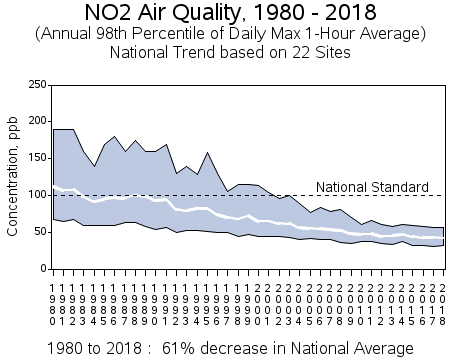

These articles show satellite photos of reductions in NO2 as evidence that air quality is improving, but these photos are not a reliable method for calculating NO2 levels during the shutdown. According to experts, the satellite photos are comparing time periods that are too short and/or reflecting insufficient filtering of data. When used correctly, they show no marked trend. Changes in the NO2 levels during the shutdown are driven mostly by clouds and seasonal changes in the angle of the sun. Currently, all parts of the United States are in attainment of the national NO2 standards, and have been since the start of the century.

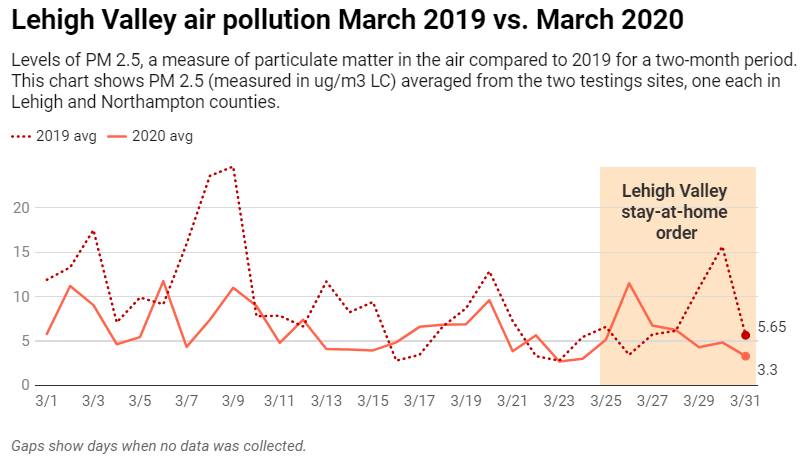

Rather than focusing on NO2, ozone and PM 2.5 should have been analyzed directly to get an accurate reading. For example, NO2 levels in Dallas declined by three percent between March 1 and April 5, but PM 2.5 levels were 24 percent higher than the five-year median. In Seattle, NO2 levels fell in March, and the level of PM 2.5 increased. In Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania, where particulate matter was measured directly, a modest year-over-year reduction was found during the time residents have been told to stay home and businesses closed to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. These latter results are not scientifically conclusive because they do not account for other factors such as weather.

Conclusion

Many factors over time influence air quality. One should not look at short time spans or only one factor to draw conclusions. Every dollar spent on the environment needs to be spent wisely because the recent economic collapse shows those dollars may be needed for more critical issues such as fighting the coronavirus or getting Americans back to work whose jobs were affected by coronavirus.

During the past five decades, the air quality in the United States has dramatically improved. The small impact from the lockdown on particulate matter and ozone indicates that our air is already clean and that adding even more costly regulations would likely provide limited benefit. To successfully identify the best ways to make additional progress, we should analyze the data and not base conclusions on misguided assumptions. The large gap between the political rhetoric and scientific reality is a reminder that costly environmental regulations should be based in real-world data, not ideologically driven assumptions or emotions.