Researchers have long thought that there was a correlation between living in urban areas and asthma prevalence. This is part of a belief that outdoor air pollution, which is often worse in inner-city areas, contributes to asthma development.

However, a new study questions the link between asthma and city living. It shows that once we adjust for other factors, notably race and poverty, whether a person lives in an urban or a non-urban area is not a good predictor of asthma.

This new research calls into question EPA’s longstanding belief that people, particularly children, who are exposed to more outdoor air pollution, such as ozone, are at a greater risk for developing asthma. Instead, the researchers found that poverty is a greater risk factor for asthma, while living in urban areas (with higher outdoor air pollution) is “not significant.”

The finding that poverty has more to do with asthma than living in urban areas undermines EPA’s case for lowering national standards for ground-level ozone—a regulation that could be the costliest rule ever proposed.

By making people poorer, EPA’s proposed rule could make asthma worse. If this study is correct, then the ozone rule would be inconsistent with EPA’s statutory requirement under the Clean Air Act to protect public health with an “adequate margin of safety.” It also underscores the need for Congress to force EPA to consider the link between economic costs and public health.

In light of this new evidence, EPA should rescind its proposed ozone rule. This rule could exacerbate the public health problem it is trying to mitigate and impose enormous economic burdens on American families. Moreover, ozone levels are already declining without further regulation, obviating the need for more federal mandates.

Study Questions Long-Held Asthma Link

EPA has long linked outdoor air pollution to asthma attacks, the “development of asthma,” and other respiratory conditions. The agency uses the assumed correlation as a pretext for nearly all of its clean air regulations, including its proposed ozone rule.

However, this new study, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology by a team of researchers led by Dr. Corinne Keet at the John’s Hopkins Children’s Center, examined data for 23,065 children across the country. The study concludes: “Although the prevalence of asthma is high in some inner-city areas, this is largely explained by demographic factors and not by living in an urban neighborhood.”

In fact, the authors found that indoor pollution linked to poverty is a greater risk factor for asthma than living in an urban area, where outdoor air pollution is usually worse. As TIME explains:

The new findings still support pollution as a cause for asthma, but it suggests that indoor pollution may be doing more of the harm.

“A lot of what may make a difference is what happens inside the home than outside the home, especially as we spend so much time indoors these days,” says Keet. Allergen exposure from old housing materials, cockroaches and mice, mold pollution, cleaning supplies, and tobacco smoke may be heavy contributors. [Emphasis mine]

The authors note in their study that once they controlled for race, ethnicity, and poverty, the correlation between inner-city living and asthma prevalence disappeared:

Here we show that although some inner-city areas have high rates of asthma, particularly in the Midwest and Northeast, other non-urban poor areas have equal or higher asthma prevalence. Overall, black race, Puerto Rican ethnicity, and poverty rather than residence in an urban area per se are the major risk factors for prevalent asthma. [Emphasis mine]

On the next page, the authors offer further explanation:

Residence in urban areas, a potential risk factor for asthma hypothesized to be mediated by exposure to indoor and outdoor pollution, pest allergens, and violence and other stressful life events, was not found to be a significant risk factor for prevalent asthma or asthma morbidity in this US population–based analysis. [Emphasis mine]

This new study isn’t the first to question the science of asthma and air pollution. Last year, Drs. Julie Goodman and Sonja Sax accused EPA of “cherry-picking” studies to support stricter ozone standards. As Goodman and Sax put it, “EPA assumes that ozone causes more health effects than what the science supports.”

This latest study casts further doubt on the scientific basis for EPA’s ozone rule. In a recent opinion piece for The Hill, Dr. Joseph Perrone, chief science officer at the Center for Accountability in Science, was the first to point out how the Hopkins study undermines EPA’s science on ozone and asthma:

This is science the EPA cannot ignore. If the agency is truly interested in “following the science,” it should spend more time addressing real public health threats than imposing costly rules based on dubious science that may only make us poorer and sicker.

It is important to note that Keet’s study examined asthma prevalence, not asthma attacks or any other health effects. EPA cites reductions in both asthma prevalence and asthma attacks to justify its proposed ozone rule.

EPA’s Ozone Rule Exacerbates Asthma and Poverty

EPA is currently accepting public comments on a proposal to tighten national ozone standards by as much as 20 percent, from 75 parts per billion (ppb) to 60 ppb. EPA Administration Gina McCarthy claims that the proposed rule is necessary because “cutting air pollution to meet ozone standards lowers the risk of asthma.”

In fact, EPA may actually make asthma worse by exacerbating poverty. A recent analysis finds that EPA’s ozone rule could slash economic growth by $270 billion per year, destroy 2.9 million jobs annually, and reduce household spending by $1,570 per year. That would make EPA’s proposal the costliest regulation in U.S. history.

If poverty contributes more to asthma than ozone, EPA’s proposal, which could put millions of Americans out of work and slow economic growth, could actually increase asthma prevalence. That would make EPA’s ozone rule inconsistent with the agency’s statutory obligation under the Clean Air Act to protect public health with an “adequate margin of safety.”

Ozone Declining Without Further Regulation

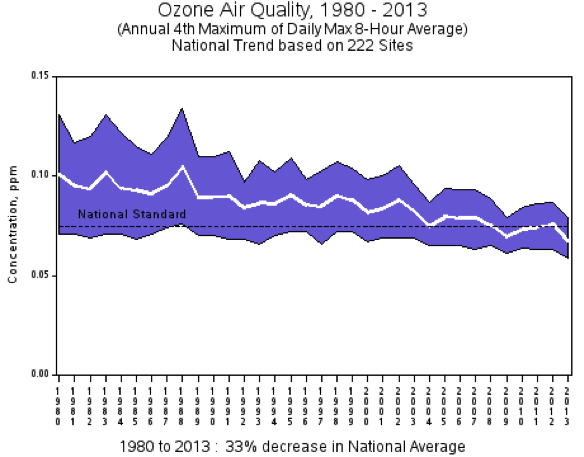

Even if EPA’s proposed ozone rule didn’t threaten public health, it would still be unnecessary because ozone levels are already declining without a tighter standard. According to EPA’s own data, ozone levels have declined 33 percent since 1980 alone. The following EPA chart shows national ambient ozone levels between 1980 and 2013:

Further tightening ozone regulations would likely only increase poverty, which could actually make asthma worse. To protect public health with an “adequate margin of safety,” EPA must rescind its proposed rule.

EPA Should Consider Link Between Poverty and Public Health

A major flaw with EPA’s ozone rule is that EPA cannot consider the link between economic costs and public health, even though the science shows that poverty worsens public health. In EPA’s Regulatory Impact Analysis for its proposed ozone rule, the agency claims “the Clean Air Act and judicial decisions make clear that the economic and technical feasibility of attaining ambient standards are not to be considered in setting or revising [National Ambient Air Quality Standards],” including ozone.

This is problematic, as it seems to conflict with EPA’s statutory requirement under the Clean Air Act to protect public health with an “adequate margin of safety.” EPA’s ozone rule could impose enormous compliance costs, resulting in job losses and reduced economic activity. In other words, the rule could make people poorer, which the science shows makes people less healthy.

Congress should force EPA to consider the link between the economic costs of its regulations and public health outcomes. EPA might still conclude that health benefits outweigh costs, but it would at least force the agency to consider the science on poverty and health.

Conclusion

The new study published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology found no link between living in an inner city—where outdoor air pollution (including ozone) is generally higher than non-inner-city areas—and asthma prevalence in children. Rather, the study found that poverty is more closely linked to asthma than city living, where outdoor air pollution is generally worse. That means EPA’s proposed ozone rule, which could be the costliest regulation in U.S. history, could actually make asthma worse by making poverty worse. In light of these new findings, EPA should withdraw its proposed ozone rule.