Crises love company. Searching “covid is lesson for climate” on Google generates millions of hits. Frustrated that the COVID crisis has supplanted their crisis, climate-Armageddon types are coming out of the woodwork with arguments of the form, “the pandemic is a crisis and climate change will be just as bad if not worse.” The ensuing prescriptions offer up lots of culture change, international cooperation, with a heavy dose of listening to the “experts” and implementing the urgent action they recommend. However, the real crisis is implementing a set of climate policies that will make the world much worse off.

In a forthcoming piece in Foreign Affairs, Nobel Laureate, William Nordhaus, also invokes the COVID crisis to provide some mojo for a climate plan he laid out in his 2018 Nobel address.

He says, “The quick spread of COVID-19 is a grim reminder of how global forces respect no boundaries and of the perils of ignoring global problems until they threaten to overwhelm countries that refuse to prepare and cooperate.”

Having hooked his issue onto the crisis wagon, Nordhaus diagnoses the major problem of climate policy and offers a two-part solution—the same carbon tax he has offered up for decades and giving climate conventions tariff authority to punish those who do not want his carbon tax.

It is worth examining all parts of his story. First, to what extent are those countries that do not buy into the extreme Kyoto policies really likely to be overwhelmed? Second, are his taxes really a good idea? Third, how sensible would it be to give tariff powers to climate agreements?

Let us begin. Nordhaus’s own analysis shows little evidence of an imminent crisis.

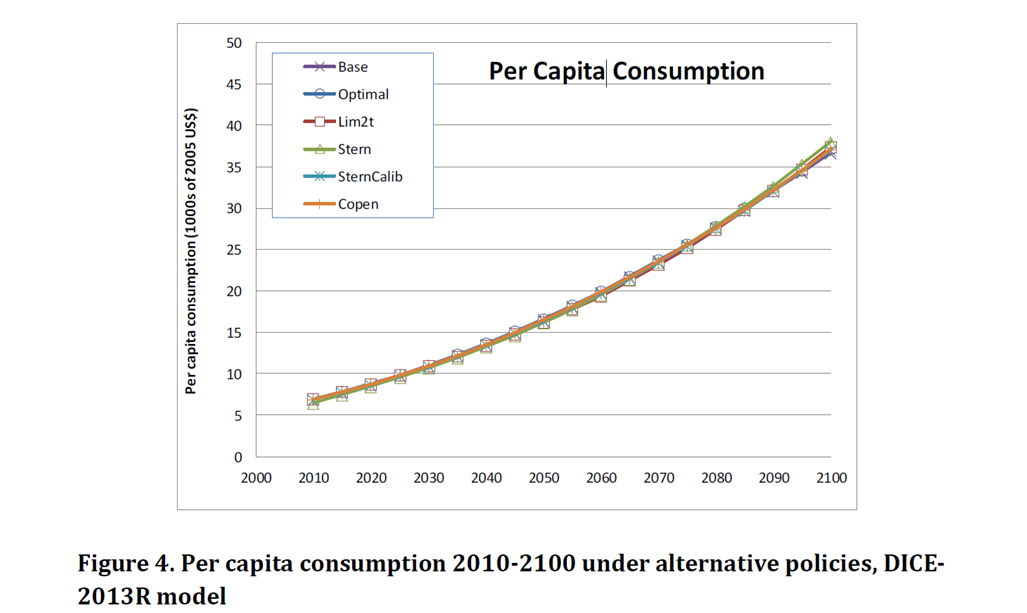

Below, is Figure 4 from the introduction and user’s manual for Nordhaus’s DICE model (Dynamic Integrated model of Climate and the Economy). It shows per capita consumption for a variety of scenarios, including no additional action (Base) and the best choice (Optimal) that uses his finely tuned schedule of carbon taxes. Consumption is broadly defined to include health, leisure, and environmental benefits. So, we are not talking about a world where people wallow in material goods while the coasts are inundated and the interior burns.

It is easy to see that between now and 2100, there is little difference between getting “overwhelmed” by doing nothing and following the optimal set of carbon taxes to get the optimal amount of CO2 reductions. The policy paths are virtually one on top of the other. “Crisis” hardly seems like the appropriate analogy.

For all the current teenage angst about lives being ruined, it is well worth noting that with or without action on the climate, lives continue to improve. When today’s 17-year-olds are middle-aged, they can expect to be about twice as well off as their scorned middle-aged parents are right now. By 2100, countries who do not follow the script will be overwhelmed by being four times better off than they are now.

The corresponding table in the handbook lets us put a finer point on the difference. Following the path to 2100 shows a four-fold increase in real per-capita consumption. The optimal-carbon tax path instead of the no-tax base path bumps per capita consumption by only two-thirds of one percent. In addition, to give this theoretical two-thirds of one percent increase to people who will be four times richer, it is necessary to cut the consumption of the poorer earlier generations.

So, what is it we need to do to the poorer current generation to win that extra 0.66% consumption bonus for the folks in 2100?

Nordhaus, like most economists, sees problems as misaligned incentives. With perfect competition and well-defined property rights, incentives are aligned and markets efficiently (though, not necessarily fairly) manage production and resource distribution. When any of these conditions do not hold, perfect efficiency no longer rules and there is said to be “market failure.”

Generations of economists have written dissertations and made a living by identifying market failures and proffering solutions. Typically, the failures are called externalities and the solutions are frequently corrective taxes to properly realign incentives. Nordhaus found his market failure in carbon-dioxide emissions and the carbon tax is his remedy. Use this one clever trick to fix the climate!

It is important to know what the solution will look like. The optimal solution is not the total elimination of an externality. In this case, that means the best remedy does not stop all anthropogenic climate change. Instead, the policy must ensure that any benefit of CO2 cuts is greater than the cost of cutting the CO2. At some point the cost of further limiting climate change is greater than the benefit. (In fact, Nordhaus’s optimal policy sees world temperature increasing way past the 1.5 and 2.0 degree C targets held as sacrosanct by the keepers of the climate flame.)

To do this sort of economic fine-tuning would require great confidence in the accuracy of the models used to determine the optimal set of carbon taxes. Or so you might think, but, in fact, that is not the case here. Uncertainties abound.

Kevin Dayaratna, Ross McKitrick, and I looked at the impact of just two of the uncertain inputs to the DICE model—the equilibrium climate sensitivity and the discount rate—and found that the DICE estimate for the 2020 carbon tax was at least 75 percent too high and possibly 238 percent too high. This is a big deal.

Remember, the carbon tax is supposed to remedy the misalignment of the cost of emitting CO2. According to the same economics that justify the carbon tax, a carbon tax that is more than 100 percent too high is worse than no carbon tax at all. That is, overtaxing carbon-dioxide emissions reduces efficiency and creates costs in excess of benefits.

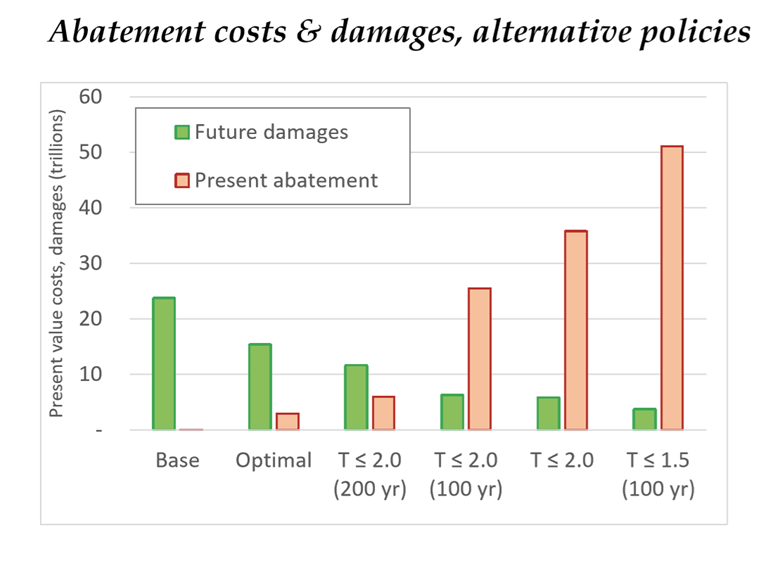

Nordhaus fully understands that a carbon tax that cuts emissions too much is not only worse than the optimal cuts, it can be worse than no cuts. We see this in the seventh slide from the deck used in his 2018 Nobel address.

The slide shows the present value of two sources of costs, summed over centuries, for the different policies. The green columns show the costs of damage from climate change. The tan columns show the costs of implementing the various policies. Adding the two columns gives the overall cost of the policies. The best policy will be the one with the lowest sum of climate costs (future damages) and abatement costs.

The fifth set of columns in the chart, “T ≤ 2.0,” shows the costs for capping temperature increase at 2.0 C. The combined costs are nearly double those of the no-policy base case. Nordhaus also includes three policies that allow temperature increases to substantially exceed 1.5 C or 2.0 C so long as the average for one or two centuries is less than 1.5 C or 2.0 C. This appears to be a bit of a subterfuge that allows the much demanded “1.5” and “2.0” to appear in the figure while allowing the temperature growth to bust the caps. In any event, even allowing such modification for the 1.5 C cap gives overall costs that are more than double those of the base, no-policy case.

This is a critical point that makes Nordhaus’s Foreign Policy recommendations virtually insane—the costs of meeting the 2.0 C target are so much greater than the climate benefits of the cap that the net effect is worse than doing nothing. In other words, the benefits of capping the world temperature increase to 2.0 C is so swamped by the costs of doing so, that it would be better to have no policy. One more time, it would be better to follow the no-policy baseline path than to be bound by a 2.0 C cap. This is what Nordhaus’s own research shows.

In short, the “overwhelmed” do-nothing policy is better than a 2.0 C cap, to say nothing of the much more costly 1.5 C cap. Hold that thought.

Here is the third point. Nordhaus claims that the great failing of climate agreements is that they did not have an incentive structure that effectively bound the members to achieving the targets. He calls his solution a “Climate Club.” Any country not implementing the agreed upon climate policy will have its exports subject to tariffs by the countries that do implement the policy. Cheaters will not prosper.

Now for the insane part: Nordhaus specifically identifies the Kyoto Protocol, whose 21st Conference of the Parties adopted the 2.0 C target; and the Paris Agreement that adopted the 2.0 C target (with an aspiration to cap the temperature increase to 1.5 C) as agreements whose failure was not their ridiculously strict targets, but their inability to force implementation of their ridiculously strict targets. Yet, according to his own analysis, meeting these caps is worse than doing nothing. Though he does not do so explicitly, Nordhaus offers a solution to ensure the success of agreements that, according to him, would be substantially worse than no agreement at all.

Instead of insanity on Nordhaus’s part, this crazy policy proposal is more likely the result of some combination of arrogance and naivety—a distressingly common problem for economists. Nordhaus proposes this enforcement structure under the assumption that it is his preferred policy that will be enforced.

Economist, James M. Buchanan, identified this problem long ago. In his Nobel address in 1986, he said, “Economists should cease proffering policy advice as if they were employed by a benevolent despot, and they should look to the structure within which political decisions are made.”

To his credit, Nordhaus is looking at the structure within which climate policy is made, but he maintains unwarranted faith that the conferees will become more like despots who are not only benevolent, but clever enough to recognize the genius of his optimal taxes. That is, his enforcement mechanism would not be implemented by the same folks who 25 meetings in a row have settled on the deeply flawed policies that are (according to Nordhous’s numbers) worse than no policy.

The various Conferences of Parties did not fail to come up with Nordhaus-optimal solutions because they had no enforcement mechanisms. They came up with ridiculous targets because they had concocted an existential crisis to justify an unprecedented power grab. The only problem Nordhaus sees with the current structure is free riding. He misses all the opportunism and the rent-seeking. Blinded to these scourges of good policy, he, in a great irony, offers a plan that could amplify both.

He suggests that any climate agreement should penalize all non-complying countries with tariffs. The Climate-Club members who adopt the requisite policy can trade freely among themselves but must impose a uniform tariff on goods from countries outside the club.

His dubious assumption is that this Climate Club would become the Optimal-Tax-and-Tariff Club and adopt his set of carbon taxes, dust off their hands and call it a day. Unfortunately for his plan, we have decades of evidence that the likely members of his club want to do lots of other things and not so much Nordhaus’s carbon taxes.

It is the bogus hyping of an existential climate crisis that gives such prominence to a climate economist in the first place. This same crisis-hype bestows heroic virtue on those pushing the overly costly policies that Nordhaus identifies as worse than nothing and provides a mantle of righteousness for self-dealing in the name of climate. Why would an enforcement mechanism change that?

The Conferences of the Parties are chock full of calls for dramatic restructuring of the world’s economies based on the faulty assumptions that socialism is less polluting than capitalism and that wealth redistribution is critical to addressing climate change. Throw in subsidies and payoffs galore and it is great fun for all. There is little from these meetings to support the notion that once weaponized, the next Conference of the Parties would replace all of this garbage with a carbon tax. It is a blessing, not a curse, that the Kyoto Protocol has so little muscle.

Economists fight a constant battle to restrain politicians from abusing tariffs. That fight will be all the more difficult if tariffs are dressed up as a solution to an existential crisis. Make no mistake, Nordhaus is hitching his policy prescription to the crisis bandwagon. He calls those opposed to climate agreements “myopic or venal” and warns they will be “overwhelmed” should they not act on climate. On the other hand, he offers no reproach for those creating hysteria in support of policies that are worse than doing nothing.

Nordhaus’s tax-and-tariff scheme is a Pandora’s Box that world leaders cannot wait to open. They should not be allowed to do so.