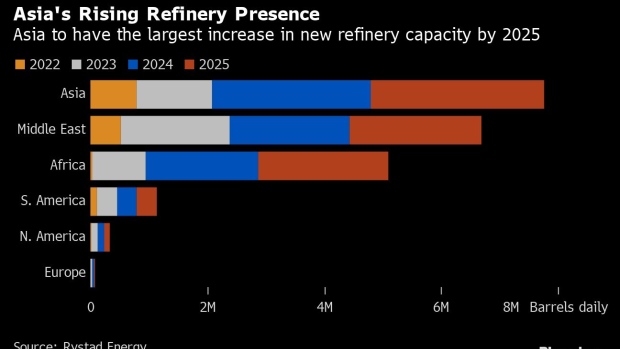

While Biden continues with his onerous regulations, Asia and the Middle East are building refinery capacity. During the COVID lockdowns with lower gasoline and diesel demand, U.S. refineries closed about 1 million barrels of capacity per day. Some converted to biofuels as generous government support for them makes their production economic. While the United States and Europe significantly cut refining capacity, Asia and the Middle East are expanding. Western markets including the Americas and Europe shut down a net 2.4 million barrels a day of refining capacity in the last three years, while the Middle East and Asia added 2.5 million barrels. That gap is expected to widen. About 8 million barrels a day of new refining capacity is set to come online in the next three years, with Asia adding the most and Europe the least.

China has been bringing larger and more sophisticated refineries online to meet the nation’s growing need for petroleum, while the United States and Europe have focused on transitioning away from fossil fuels. Many new refinery projects in Asia have also been constructed due to the region’s growing petrochemical demand. For nations without sufficient refinery capacity, however, fuel security concerns are at the forefront as a refinery outage will have a greater impact on supply and prices. As such, European governments and their citizens plagued with massive utility bills and soaring inflation are now prioritizing energy security requirements over the next few years rather than the 2040 to 2050 period when they intend to be at net zero carbon. However, interestingly, the renewable energy sources and consumption methods the Western countries support are much more concentrated in Asia and specifically China than any other world energy source.

The West is feeling the strain of having fewer refineries. Northwest Europe’s stockpiles of diesel are dwindling, and will reach their lowest at the start of spring, as the European Union intends to cut off seaborne imports of Russian fuel in February. And, shortages of diesel and gasoline on the U.S. East Coast are making President Biden consider a mandate requiring oil companies to store more fuel domestically and possibly banning petroleum exports. The gasoline crunch may worsen next year.

Latin America has become more reliant on imports as several refineries in the Caribbean shuttered and another in St. Croix is being impacted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency requiring more environmental control technology and a Prevention of Significant Deterioration permit, which will take years and hundreds of millions of dollars to satisfy. It may convince owners to abandon plans to restart one of the largest refineries in the world, which incidentally is exempt from the Jones Act. Facilities in Venezuela and Mexico continue to experience significant outages and low run rates. Mexico is importing gasoline from China, where refiners are taking advantage of higher export quotas by running harder and exporting more. Asia’s exports of transport fuels to the Americas is currently more than double that of year-ago levels. China is cashing in on its investments in refineries.

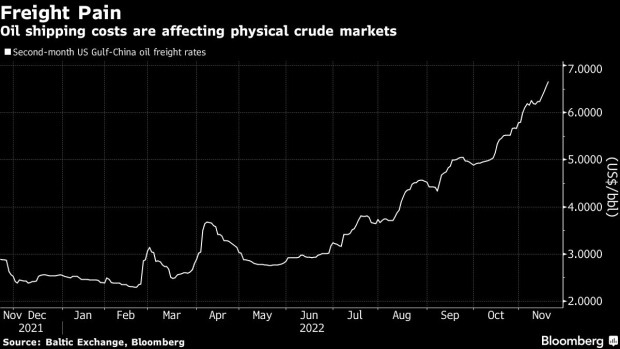

The hauling of petroleum products westward across longer distances is sharply increasing shipping costs and driving a rally in tanker earnings. The volume of fuel transported by sea is 3 percent higher than averages seen in the last five years, led by diesel from Asia and the Middle East to Europe. Those volumes may expand as Europe bans Russian supplies.

Freight Costs

Earnings on the industry’s benchmark trade route recently breached $100,000 a day— the highest since early 2020 when Covid-19 caused a surge in tankers storing cargoes. Western sanctions on Russia are forcing ships to take longer routes — using up the pool of available vessels, which results in higher prices to transport cargoes that is added to the cost of shipping oil and petroleum products. U.S. Gulf shipments to China, one of the industry’s longest-distance mainstream routes, now cost about $6.60 a barrel--almost three times the cost in February and almost 16 cents per gallon.

The escalating shipping costs, however, are being offset by falling spot premiums even for OPEC producers. Oil from the Persian Gulf is in more demand by Asian buyers when freight rates surge as refiners and traders try to obtain more-local supplies rather than long-haul grades from the Atlantic Basin. The West African oil market is being hit hardest by surging freight rates as more than half of its cargoes are shipped to faraway locations including China and India.

The shrinking availability of tankers not only causes a surge in freight rates, but also increases the rates for demurrage — the costs of delays in and around ports. Demurrage costs for very large oil carriers are now estimated at about $120,000 to $130,000 a day, up by about $50,000 from two months ago. To minimize that, many cargoes are trying to arrive at ports just in time for loading.

On December 5, the European Union and the United States plan to place a cap on Russian oil prices that shipping companies and insurance providers are to implement. The actual cap level has not yet been set, making it hard for buyers to plan how much they might want to purchase from Russia and causing more uncertainty in the market. This presents potentially profitable arbitrage opportunities for those trading. The turndown in China’s oil purchases because of their zero-covid policies has given Europe extra time to work out how to replace around 800,000 barrels a day of Russia’s Urals oil after the E.U. embargo on the OPEC+ producer’s imports takes effect.

Conclusion

As Europe and the United States shutter their refineries, Asia, the Middle East and Africa are building more refining capacity. This should bring up security of supply concerns for Western countries, who are more concerned with climate change issues and destroying fossil fuel markets than having adequate supplies of petroleum products that are needed now. Europe is headed to a diesel shortage and the United States has one on its East Coast, which has shuttered much of its refineries and are limited in obtaining supplies form the U.S. Gulf coast because of the Jones Act. The Jones Act does not allow U.S. supplies of diesel to reach other regions of the United States by sea unless those supplies are on U.S. tankers manned by U.S. workers. The situation will just get direr in the future unless the United States and Europe change their near-term position on their policies on energy and climate change and their environmental regulations.