“Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.” This adage, often attributed to economist Milton Friedman, rings particularly true today concerning energy subsidies. Time and again, subsidy mechanisms like tax credits and production mandates are introduced with specific expiration dates or phase-down schedules, framed as temporary boosts for nascent technologies or short-term solutions to specific problems. Yet, history shows these policies are not temporary, with Congress granting “temporary” extensions year after year after year.

Congressional Republicans are reportedly considering a “phase down” of the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) green energy subsidies. But history shows there is no such thing as a “phase down” of these policies because they will inevitably be resurrected. If the goal is to protect taxpayers from never-ending subsidies and protect the electric grid from the destabilizing influence of the Production Tax Credit (PTC) and Investment Tax Credit (ITC), these tax credits need to be ended now.

The IRA’s Tax Credits are Very Expensive

Analysis from the Treasury Department shows that the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) for wind and the Production Tax Credit (PTC) for solar are already the most expensive energy-related tax expenditures, projected to cost $31.4 billion in 2024 alone. Since 2015, their 10-year cost has grown 21-fold, and by 2034, they’re expected to make up more than half of all energy tax provisions.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) put these subsidy programs into overdrive, extending their timelines and ensuring that the American energy economy becomes a politically driven race to the bottom. The Cato Institute projects that the IRA’s total green energy subsidies will potentially reach between $2.04 trillion and $4.67 trillion by 2050. These figures reveal how dramatically the original 10-year cost estimate by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) missed the mark. Independent analyses, including a $1.2 trillion estimate from Goldman Sachs, land well within Cato’s projected range and suggest the actual cost over the next decade could be roughly triple what the CBO projected when the IRA was passed. Additionally, the Tax Foundation estimates that repealing the Inflation Reduction Act’s green energy tax credits could return $851 billion to federal coffers over the next decade. Supporting this, an EY analysis finds that cutting the EV tax credits alone could save about $300 billion between 2026 and 2035.

The IRA’s Tax Credits Harm the Reliability of the Electric Grid

However, these figures don’t explain the total harm of the IRA. These tax credits distort electricity markets to the point where wholesale power prices can turn negative, forcing other generators to pay the grid to accept their electricity. While wind and solar producers still profit thanks to the subsidy, conventional power plants like coal, natural gas, and nuclear facilities operate at a loss under these conditions. As a result, many of these baseload generators have been forced to shut down, even as electricity demand is expected to climb due to the rapid growth of AI data centers and manufacturing. This loss of reliable generation capacity is straining supply just as demand surges, leaving major energy users scrambling to secure dedicated power sources.

“Temporary” Tax Credits are never Temporary–A History

Examining the histories of the Wind Production Tax Credit, the Solar Investment Tax Credit, the Biomass-based Diesel Tax Credit, and federal Electric Vehicle (EV) tax credits reveals a clear pattern: policies designed to sunset will find ways to endure.

The initial designs of these subsidy programs originally included plans to phase them out:

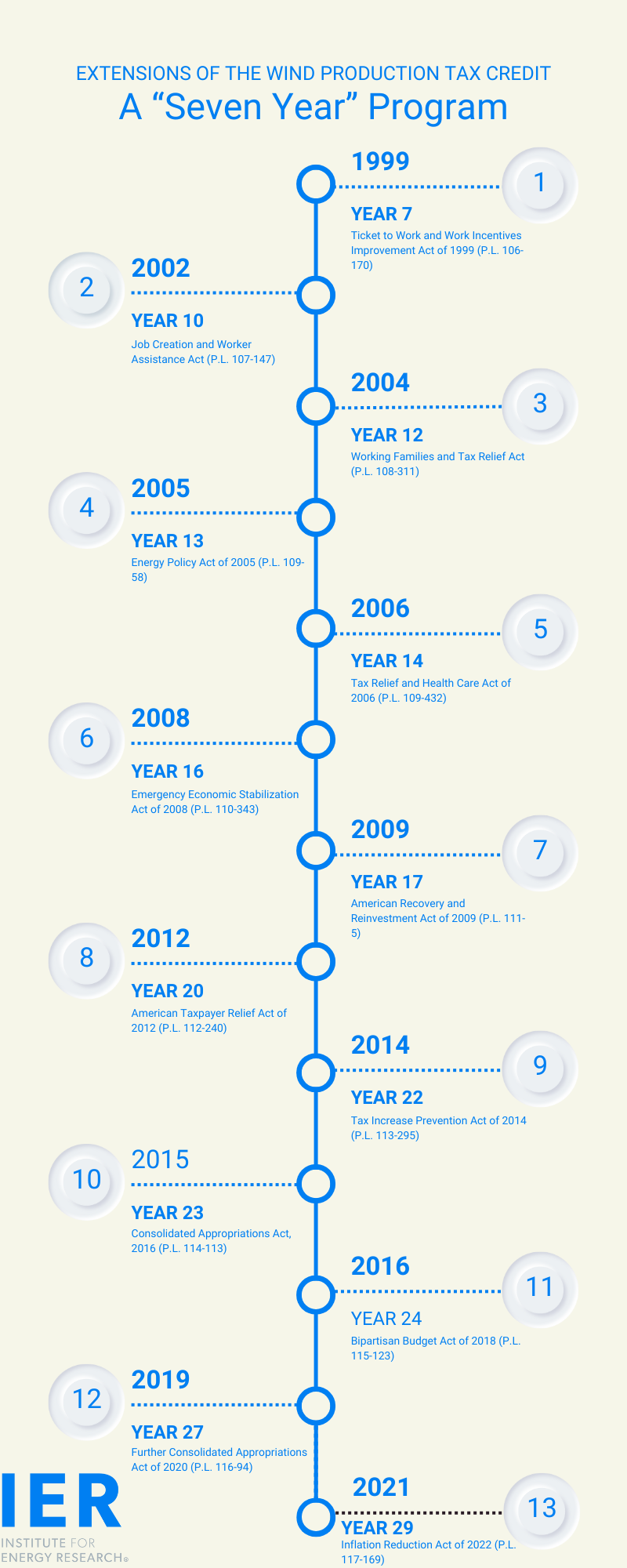

- The Wind PTC, enacted in 1992, was explicitly scheduled to expire in 1999 and was intended to nurture a “nascent” wind industry.

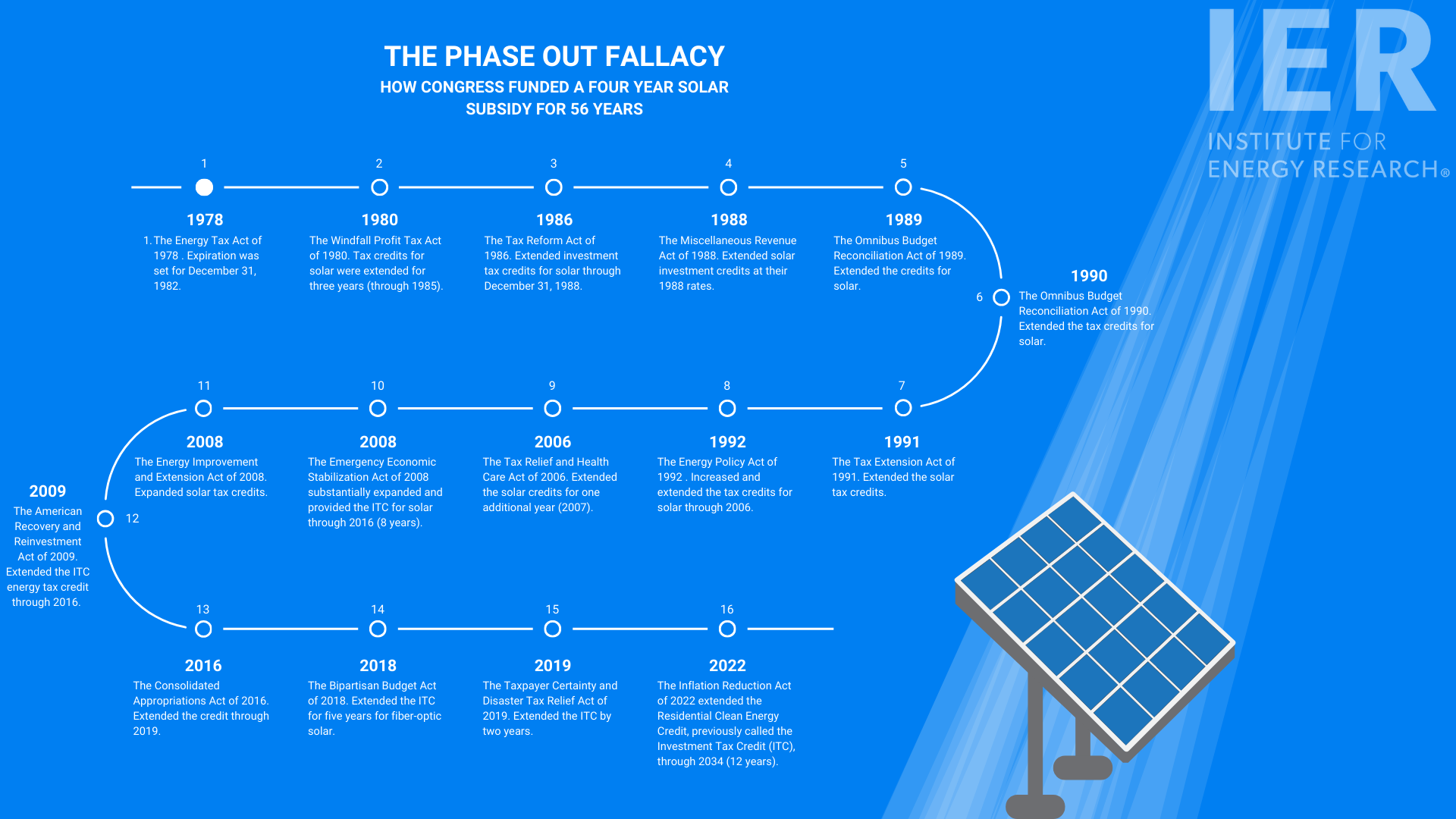

- The Solar ITC, originally introduced in 1978, was boosted significantly in 2005, came with a 2007 expiration date, and was later extended to 2016 with a clear phase-down path envisioned from there.

- The Biomass Diesel Tax Credit was created under the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004. It expired in 2013 but was retroactively reinstated in 2014.

- Early EV tax credits (like the 2005 hybrid credit) had explicit end dates (e.g., Dec 31, 2010), and the landmark 2009 EV credit included a per-manufacturer vehicle cap (200,000) specifically designed to trigger a gradual phase-out once a certain market penetration was achieved.

In each case, the architecture pointed towards a limited duration, but all of these programs have been expanded and extended multiple times, and they all continue to exist today.

Initially set to expire in 1999, the wind PTC was extended in 1999, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2019, and 2021. The 2016 extension of the PTC was even structured as a phase down, with the value of the PTC stepping down each year by 20% for five years, supposedly to terminate then. However, the IRA extended the PTC in a way that was perhaps the most egregious. The IRA creates a “phase out” of the PTC starting in 2035 or two years after the U.S. electricity sector achieves a 75% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from the 2022 baseline, whichever date is later. The U.S. electricity sector will not meet that target by 2035 (or likely ever), making the PTC the perfect encapsulation of the phase-down fallacy.

Likewise, the solar ITC’s phase-down has been repeatedly delayed and reset, most recently by the IRA, pushing its scheduled expiration well into the 2030s. The early history of the solar ITC included 7 laws and 6 extensions:

- The Energy Tax Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-618) created a “temporary” 10 percent tax credit for business property and equipment using energies other than [thought to be rapidly depleting] oil or natural gas. Tax credits for solar were refundable (e.g., credits could be received as a payment if the taxpayer could not offset his or her tax liability). Expiration was set for December 31, 1982.

- The Windfall Profit Tax Act of 1980 (P.L. 96-223) expanded the energy credit to subsidize qualifying renewables. The prior tax credits for solar were extended for three years (through 1985) and increased to 15 percent. The credit was made nonrefundable.

- The Tax Reform Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-514) extended investment tax credits for solar (and geothermal) with a phase-down to 10 percent before being set to expire December 31, 1988. The credit for wind was not extended.

- The Miscellaneous Revenue Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-647) extended the solar, geothermal, and ocean thermal investment credits at their 1988 rates.

- The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 (P.L. 101-239) again extended the credits for solar (and geothermal and ocean thermal).

- The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-508) extended the tax credits for solar (and geothermal).

- The Tax Extension Act of 1991 (P.L. 102-227) again extended the solar (and geothermal) tax credits.

More recently, since 1992, there have been 9 extensions and modifications to the solar ITC:

- The Energy Policy Act of 1992 (P.L. 109-58) increased the ITC from 10 percent to 30 percent for commercial/residential solar through 2006.

- The Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-432) extended the above credits for one additional year (2007).

- The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-343) substantially expanded and provided the ITC for solar through 2016 (8 years).

- The Energy Improvement and Extension Act of 2008 expanded the new solar tax credits for Solar Water Heat, Solar Space Heat, Solar Thermal Electric, Solar Thermal Process Heat, Photovoltaics, and Solar Hybrid Lighting with a home-use cap of $2,000.

- The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5) modified and extended the ITC energy tax credit through 2016. The $2,000 cap was removed.

- The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-113) extended the credit through 2019. The termination date was changed from a placed-in-service deadline to a construction start-date phaseout, with 26 percent for construction beginning in 2020, and 22 percent for construction commencing in 2021.

- The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123) extended the ITC for five years for fiber-optic solar (as well as fuel cell, small wind, microturbine, CHP, and geothermal heat pumps). These energies were eligible for a 30 percent credit through 2019, with rates declining with construction dates.

- The Taxpayer Certainty and Disaster Tax Relief Act of 2019 (P.L. 116-260) extended the ITC by two years.

- The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 extended the Residential Clean Energy Credit, previously called the Investment Tax Credit (ITC), through 2034 (12 years). The credit was increased to 30 percent (from 26 percent). Thirty percent of solar panel purchases were deductible from the total cost of federal taxes. The residential solar tax credit is scheduled to drop to 26 percent in 2033 and 22 percent in 2034.

The biomass-based diesel tax credit, which received a comparatively stingy 2-year extension from the IRA, has seen 6 extensions since its creation in 2004. Additionally, the EV tax credit’s manufacturer cap was eliminated by the IRA, replaced with a new set of complex requirements and a 2032 expiration date – essentially restarting the “phaseout” clock under different rules.

Why the IRA Energy Subsidies May Never Go Away—Unless We Act Now

If federal energy subsidies aren’t repealed now, they may never be. The longer these programs remain in place, the more politically entrenched they become, with growing coalitions of beneficiaries and justifications working to ensure their survival. There are four factors that will ensure these programs survive any alleged plans to phase them down.

First, consider path dependency and vested interests. Once projects like wind farms, solar arrays, ethanol plants, and electric vehicle factories are built with the help of subsidies, industries quickly form around them—and so do powerful lobbying groups. Trade associations like the American Clean Power Association (formerly the American Wind Energy Association), the Solar Energy Industries Association, and the Renewable Fuels Association have become highly effective at securing extensions for the subsidies that benefit their members. The political math often favors them: concentrated benefits for a few are easier to defend than diffuse costs borne by millions of taxpayers or consumers.

Second, the purpose of these subsidies keeps evolving. The history of American energy policy is rife with examples of shifting policy rationales that serve entrenched interests but hurt the American people. Initially pitched as temporary boosts for fledgling technologies or ways to enhance energy security, today they’re justified by broader political goals—chief among them, fighting climate change. Rural job creation, farm income support, domestic manufacturing, and even labor standards have since been added to the list. This ability to adapt to shifting justifications for abysmal policies allows subsidy schemes to persist.

Third, the “market stability” argument has become a potent tool. Advocates routinely warn that letting subsidies lapse would disrupt investments, create boom-bust cycles, and slow progress. These fears often prompt Congress to extend incentives for just a few more years, with vague promises of phasing them out later. In practice, such “phase-downs” serve as political cover—buying time for the conversation to shift and for another round of extensions to be passed. Most importantly, there is nothing “stable” about an economy organized around political favors and rent-seeking.

Finally, these programs are not just extended—they’re reinvented. Today’s subsidy regime is far more complex and embedded than it was a decade ago. Tax credits have evolved into hybrid structures, offering cash grants or bonus incentives for meeting certain labor or sourcing requirements. Electric vehicle credits now hinge on where cars are assembled, what materials go into their batteries, and even who’s buying them. These adaptive mechanisms don’t just prolong subsidies—they hardwire them into broader industrial and climate policy frameworks, making repeal even harder.

While supporters claim these incentives bring long-term stability to energy markets, they ignore the broader distortionary effects. Propping up industries regardless of real market demand creates economic inefficiencies and misallocates capital, risks that grow the longer subsidies remain disconnected from actual consumer needs.

The Road Ahead

The evidence is clear: so-called “temporary” energy subsidies rarely go away. Instead, they’re repeatedly extended, rebranded, or repurposed—turning into permanent fixtures of federal policy. The phase-out narrative has become little more than a political smokescreen, used to deflect criticism while paving the way for future extensions.

The Inflation Reduction Act represents the latest and most sweeping expansion of this dynamic. The cost is staggering, the market distortions are mounting, and the promised benefits remain largely speculative. Meanwhile, entrenched interests and evolving justifications—from climate change to job creation—continue to shield these subsidies from meaningful scrutiny. If lawmakers are serious about restoring fiscal responsibility and ending the cycle of politicized energy policy, they must reject the comforting fiction of the phase-out. The only way to truly rein in wasteful, distortionary spending is through full and permanent repeal.