The Production Tax Credit (PTC) for wind energy is set to expire at the end of this year. In March the Senate failed to pass Sen. Debbie Stabenow’s (D-MI) measure that would have extended the PTC (and other renewables tax credits), while Sen. Robert Menendez’s (D-NJ) bill and a bipartisan House bill are still pending. This morning, Politico reported on the ongoing fight that many Democrats and some Republicans are making to renew the PTC

The present post will summarize the history of the PTC. We will see that despite the billions in tax advantages the wind industry has received over the decades, it hasn’t delivered anywhere near the promises of its proponents. If Congress wants to stimulate job creation and energy production through tax policy, it should avoid picking winners and losers, and instead apply a uniform tax code with as low a rate as possible to all energy sources.

A Brief History of the PTC

According to the fact sheets provided by the EIA and American Wind Energy Association (AWEA), the federal government supported wind power through an Investment Tax Credit (ITC) as far back as The Energy Tax Act of 1978. The modern Production Tax Credit (PTC) was established in the Energy Policy Act of 1992. The PTC “provided an inflation-adjusted tax credit of 1.5 cents per kilowatt-hour for generation sold from qualifying facilities during the first 10 years of operation.” (Currently the PTC is 2.2 cents per kWh.) In addition to wind, over the years Congress has extended eligibility to geothermal, certain hydroelectric, “open-loop” biomass, landfill gas, and even marine energy resources.

The status of the PTC was most recently amended by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, more commonly known as the Obama stimulus package. In this legislation the PTC for wind was extended through December 31, 2012 (and through 2013 for other renewables). Alternatively, the ARRA gave project owners the option of receiving a 30% Investment Tax Credit (ITC) rather than (not in addition to) the PTC. Developers can receive the 30% ITC as a cash payment from the Treasury, for projects where construction started before the end of 2011 and that are placed in service before 2013. ARRA also created the t section 1603 program which allowed developers to elect to receive cash rebates in lieu of tax credits, but only if construction had begun before the end of 2011.

Putting Wind Growth in Perspective

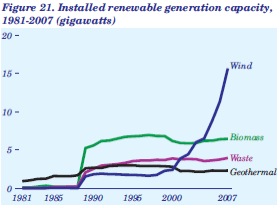

Certain graphical presentations might give the appearance that wind power is a mushrooming component of the U.S. energy mix, and that just a few more years of government support will ensure its rightful place among other sources. For example, consider the following chart from the EIA:

This graph certainly makes wind look impressive, until we realize that its current capacity is only large when compared against (a) wind’s capacity in earlier decades or (b) the current capacity of other, obscure renewables.

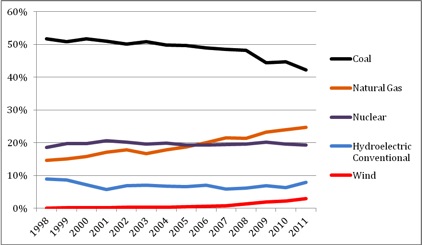

Furthermore, looking at capacity can be misleading because wind’s capacity factor is lower than that of more traditional sources. We get a much different perspective if we chart the trends in total U.S. electricity generation by source (again using EIA data):

Net Electricity Generation By Energy Source, as % of U.S. Total, 1998 – 2011

Source: Energy Information Administration

As the chart above shows, wind is still very much a niche energy source. The other non-traditional renewables sources wouldn’t even register. For example, geothermal accounted for 0.4% of U.S. electrical generation throughout the period, while solar accounted for 0.01% early on, but by 2011 had risen to a whopping 0.04%.

The Utter Dependence of Wind On the Tax Code

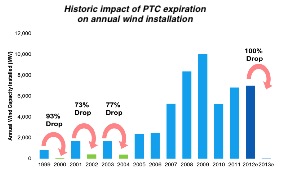

Recognizing what Americans’ priorities are in a time of severe recession, proponents of extending the PTC for wind and other renewables now talk as if it’s a matter of jobs. Yet the AWEA’s own graph [.pdf]—intended to show the urgency of Congressional action—shows just how dependent the wind sector is on federal advantages:

SOURCE: AWEA

It’s true, the AWEA’s chart shows that the PTC is essential for maintaining the continued growth in wind capacity. However, the chart also shows that wind has been a ward of the government for (at least) 13 years. At what point is wind power supposed to hold its own in the marketplace, without special tax treatment? The above chart is exactly what we would expect to see, if government policies were grossly inflating the size of the wind sector above its efficient role in the economy.

As Lisa Linowes points out, the implicit federal support (via the PTC) for wind has mushroomed over time, rising from $5 million in 1998 to more than $1 billion annually today. Furthermore, even if Congress does nothing and allows the PTC for wind to expire this year, the government is still locked in to nearly $10 billion in tax credits for previous, qualifying projects. To see just how massive the implicit subsidy is, Linowes observes that the 2.2 cents per kWh tax credit is effectively a gift of 3.7 cents per kWh of taxable income—higher than the wholesale price of electricity in many regions of the country.

Conclusion

The Institute for Energy Research seeks to educate policymakers and the public on the benefits of free-market solutions to energy issues. As such, IER is well aware of the connection between low taxes, job creation, and energy production.

Even so, the arguments for Congress to “create jobs” through extending the renewables PTC are weak indeed. The only reason wind has gained the (small) market share it has, is that Congress simultaneously taxes competing forms of energy while offsetting this onerous burden through the PTC. If the government extended the PTC for wind and other renewables, and applied it to coal- and natural gas-fired power plants as well, then there would be an expansion of total capacity and electricity prices would tumble for consumers. At the lower prices, even with the PTC, once again wind and other renewables would not be able to compete, and they would shrink back to their efficient niche.

It makes sense to cut taxes to support job growth and energy production. However, the most efficient and least politicized approach would be to engage in evenhanded reform where government officials don’t pick winners and losers. If wind power is as cutting edge as its proponents claim, then it should be able to survive on a level tax- and regulatory playing field.

###