A U.S. federal appeals court partially reversed a judge’s order upholding an environmental analysis of two offshore oil and gas lease sales held in 2018 that span over 150 million acres in the Gulf of Mexico. The lease sales, 250 and 251, were among 11 proposed by the Interior Department in its 2017 five-year plan. Environmental groups had previously failed to convince a lower court that the Interior Department’s analysis was inadequate. On appeal, the D.C. Circuit found a shortcoming with Interior’s environmental impact statement for the sales but otherwise found the agency had complied with federal law. The judge declined to vacate the supplemental [environmental impact statement], the records of decision announcing Lease Sales 250 and 251, or the leases issued through those sales. The ruling sends the case back for further consideration by the Interior Department’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

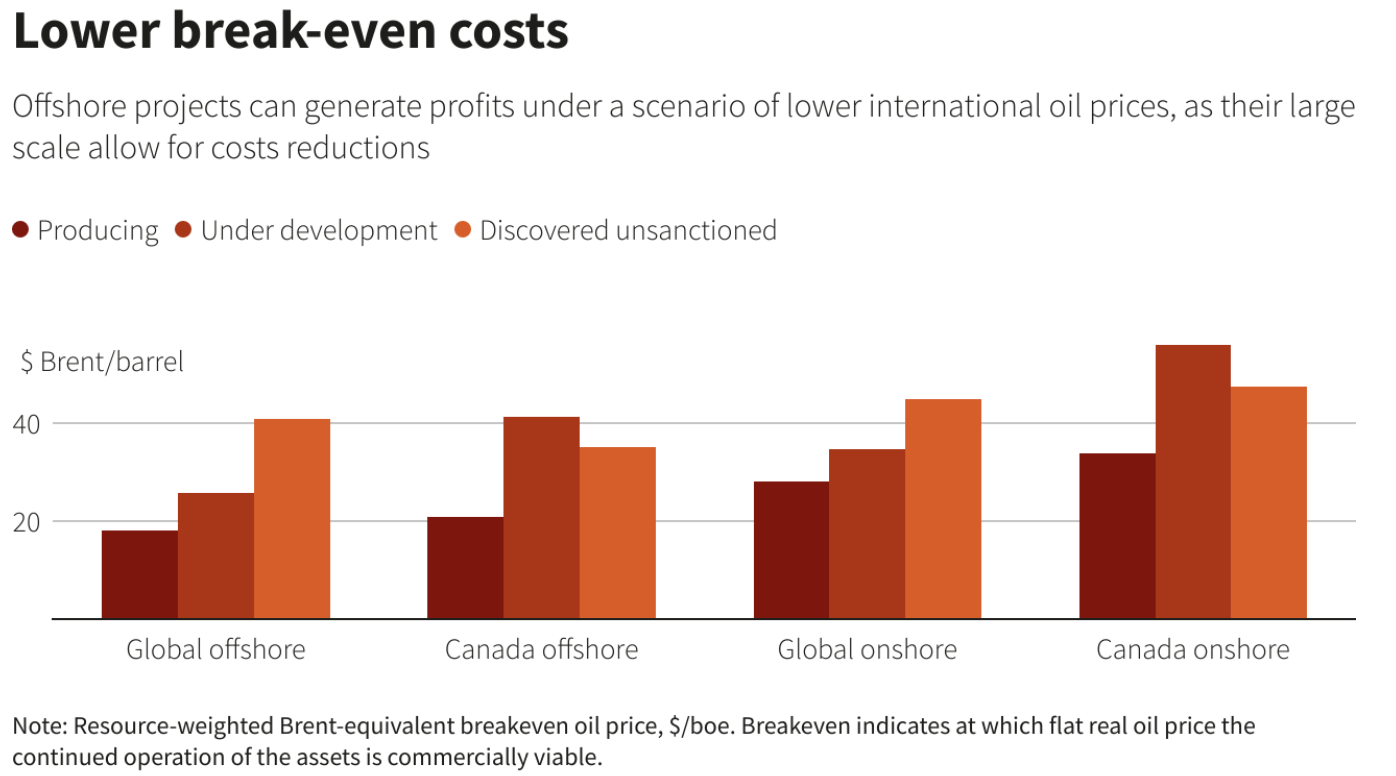

While environmental groups in the United States are suing the federal government over offshore lease sales and the Biden Administration continues its “pause” on leasing, the rest of the world is investing in offshore oil development. Global oil companies are spending billions on offshore drilling due to surging oil prices and because the projects can produce oil for decades. Global offshore investment is expected to increase 27 percent from 2021 levels to $173 billion in 2024, reversing a decade of decline and growing slightly faster than onshore investment. Because of their large scale, offshore projects have lower break-even costs and fewer emissions per barrel than onshore projects. Producing offshore projects average a break-even price of $18.10 per barrel of oil equivalent, compared with $28.20 per barrel for onshore projects. (See figure below.)

A Canadian Offshore Project

Projects being considered include remote icy waters far off Canada’s Atlantic coast. Norway’s Equinor ASA is close to a final decision on its Bay du Nord project 311 miles offshore off Newfoundland and Labrador. The project, costing $12.37 billion, would include a floating production storage and offloading unit (FPSO) that would measure more than a city block. The project is so far offshore that helicopters flying in workers for three-week shifts might carry only eight people, half the usual number, to account for extra fuel. If approved, Bay du Nord could produce oil by 2030. The offshore site falls in international waters, requiring Canada to pay United Nations royalties. It illustrates how far offshore producers are willing to go seeking oil supplies and at what costs.

The Canadian government approved Equinor’s Bay du Nord in April, saying it raised no significant environmental issues, despite Canada’s commitment to the Paris climate accord. Canada could approve more such projects as long as they produce low emissions, have best-in-class technology and can reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Bay du Nord is expected to produce below 8 kilograms per barrel of carbon dioxide–less than half the international average. New technology also makes it easier to curb flaring and methane emissions and recycle heat.

There are challenges, however, associated with its location. Bay du Nord would be producing oil in icy waters known for waves up to 15 meters high in winter. Icebergs float across the area between March and July, and two species of endangered sea turtles inhabit its waters. Canada, however, already has profitable producing fields far offshore with similar weather that are at greater depth. Bay du Nord’s water depth of 650 to 1,170 meters is much less than wells elsewhere at 3,000 meters.

Bay du Nord might be the first of several large Newfoundland offshore projects. OilCo, a Newfoundland government corporation, has identified 20 prospective projects, each with 1 billion barrels in reserves. Other companies have bought into Canadian projects this spring. BP PLC purchased a Bay du Nord stake and Cenovus Energy restarted a stalled project. European oil majors are setting similar offshore goals. Both Shell and BP say they plan to reduce oil output over time but will keep investing heavily offshore, and each is adding a new Gulf of Mexico platform this year.

U.S. vs. Global Offshore Oil Production

Offshore oil production accounts for about one-third of world oil output, but just 15 percent of U.S. 2020 oil production. President Biden has shown that he wants to reduce that further as he cancelled three offshore lease sales this year—two in the Gulf of Mexico and one in Alaska’s Cook Inlet and did not challenge the only offshore lease sale in the Gulf of Mexico that his administration held last year, which was invalidated by a federal judge, claiming that the sale did not appropriately consider climate change. The Alaska lease sale would have covered more than 1 million acres that would provide oil for 40 or more years of production. Further, the Energy Information Administration found that the oil from new offshore fields coming on line will not offset oil production declines expected in the Gulf of Mexico, indicating how important these lease sales are to continuing oil production offshore.

The Lawsuit against Two 2018 Offshore Lease Sales

A coalition of environmental groups argued that the Trump administration’s evaluation of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) had erroneously presumed adequate endorsement of safety and environmental procedures in the Gulf. On April 20, a D.C. court sided with the Trump Interior Department, which prompted an appeal by the plaintiffs: Earthjustice, the Sierra Club and the Center for Biological Diversity. In the ruling, the appeals court judge sided with the plaintiffs, stating that the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management failed to consider whether the federal Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement’s “work was in fact rigorous, despite some evidence that it was not” when it came to inspection and enforcement, noting a Government Accountability Office report that said the procedures are outdated and inconsistent. The judge sent the case back for further consideration by the Interior Department’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, but declined to vacate the leases issued through the sales.

Conclusion

Despite U.S. offshore oil production being a smaller fraction than global offshore oil production, environmental groups and the Biden Administration want to reduce that share even more. The U.S. pioneered offshore oil and gas exploration, development, and production, but it is yielding its lead. Based on a lawsuit from environmental groups, an appeals judge recently sent back to the Department of Interior two lease sales that occurred in 2018 for further consideration regarding safety and environmental procedures in the Gulf.

The Biden Administration canceled three offshore lease sales and has not challenged a lease sale that was invalidated by a judge for not adequately considering climate change. While Senator Manchin has included restitution of these lease sales in the Inflation Reduction Act, there is no insurance that they will not face legal challenges, resulting in the need for the Biden Administration to challenge the negative rulings. While the world is seeing that oil and natural gas are needed for decades, President Biden is trying to do away with the fuels as he said when he campaigned. Even Elon Musk told European energy leaders that the world needs more oil and natural gas, while proceeding with the renewable transition.