Key Takeaways

AI data center electricity demand is growing, not only in the United States, but worldwide, with it expected to reach 20% of global electricity demand by 2030-2035.

Under this significant growth in electricity demand, grid operators are concerned about stability and reliability as data center workloads can change in seconds.

Some utilities such as Dominion Energy are adding capacity to meet the growing demand while, in other cases, developers are obtaining their own power.

Utilities and developers are looking to natural gas generation or nuclear power to supply reliable electricity 24/7.

Virginia, known as “Data Center Alley,” is the world’s top data center market due to its geographical location and robust fiber optic cable infrastructure.

According to Penn State’s Institute of Energy and the Environment, in 2023, artificial intelligence (AI) data centers consumed 4.4% of electricity in the United States, which could triple by 2028. By 2030-2035, data centers “could account for 20% of global electricity use, putting an immense strain on power grids.” There are more than 10,000 data centers globally — huge warehouses containing thousands of computer servers and other infrastructure for storing, managing, and processing data. Over 5,000 data centers are in the United States with new ones being built every day. As explained by the American Action Forum, Virginia, known as “Data Center Alley,” is the world’s top data center market due to its geographical location and robust fiber optic cable infrastructure. This rapid growth is causing grid volatility, as data center workloads can change in seconds, challenging grid stability and requiring reliable generating technologies to handle the demand.

Data centers are not alone in increasing electricity demand; the electrification of vehicles, heating systems, and industrial processes, pushed by the Biden administration, are also having an impact. Along with increased electrification, the Biden administration implemented policies designed to eliminate fossil-fuel-based energy in favor of taxpayer-subsidized solar and wind facilities. Wind and solar, however, cannot provide power to AI data centers solely by themselves as they are intermittent, producing power only when the wind is blowing and the sun is shining. Data centers, however, require power 24/7, resulting in the need for increased natural gas and nuclear power — the latter, most likely in the form of small nuclear reactors. Exxon Mobil wants to supply natural gas to power generators serving data centers, but only if that electricity can be decarbonized through carbon capture and storage or other technologies. Exxon and Chevron earlier this year announced plans to enter power-supply markets.

Electric utilities in regions that already have a number of data centers — like Virginia — are hitting capacity limits, and many utility CEOs are worried about the pace and scale of new AI-related load requests. Because meeting these new demands often requires massive upgrades to transmission infrastructure, which can take five to ten years to permit and build, the challenge is not only technical, but also political. Permitting reform is needed, but Congress has so far failed to produce it. Utility companies are having to determine where and how to build new generation, how to plan for grid expansions, and how to regulate and forecast demand in areas friendly to their needs, without relying on traditional demand models that rely on historical trends.

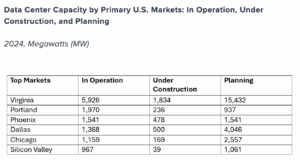

According to the American Action Forum, Virginia currently leads the market for data centers in the United States, with 5,926 megawatts of operational capacity, 1,834 megawatts of capacity under construction, and 15,432 megawatts of planned capacity. According to Dominion Energy, the state’s largest utility, data centers will be the key driver for growing energy demand in Virginia over the next 15 years. The utility company plans to invest $50 billion between 2025–2029 to support the growth of data centers in the region. Virginia’s data centers consumed about 34 million megawatt hours in 2023, 35% higher than data centers’ electricity consumption in the second ranking state, Texas, and more than three times the amount as the third-ranking state, California. Approximately 80% of Virginia’s data centers are located in Loudoun County in Northern Virginia.

The PJM Interconnection, whose mission is to ensure reliability in 13 states, including Virginia, is developing rules for interconnecting data centers and other large loads to its system while ensuring the region has enough power supplies. Its plan is to develop a proposal to be filed for approval with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission by the end of the year. That timing would allow the rules to be in effect for PJM’s 2028/2029 base capacity auction to be held in June. The effort will focus on four main issues: resource adequacy, reliability criteria, interconnection rules, and coordination. An energy watchdog found that the grid operated by PJM Interconnection has no spare supply for new data centers and suggested developers build their own power plants, which some are doing. Already, some developers are selling surplus energy on the wholesale market. Over the past decade, the sales have totaled $2.7 billion, with most of that revenue generated since 2022.

Analysis

Clearly, demand for AI is growing and utilities are ill-prepared to meet the cost and reliability challenges this growth will bring. While an adverse permitting landscape plays a significant role in delaying utilities’ ability to connect new generation to the grid, the lack of competition utilities face should also be considered a hindrance to progress. One solution to this problem is the creation of privatized grids that are physically unconnected to existing grids, allowing them to avoid byzantine regulatory and administrative processes. As Travis Fisher, director of Energy and Environmental Policy Studies at the Cato Institute, explains, “At the societal level, the obvious upside to allowing competition is that we could finally bring a dynamic market process to the electricity industry. Who knows what innovations entrepreneurs could bring to the industry if they didn’t have to ask for permission from regulators?” By bypassing bureaucratic barriers and creating competition, privatized grids provide a commonsense solution to meeting growing demand without burdening consumers with higher costs.

For inquiries, please contact [email protected].

“This piece was edited on 8/28/25 to include an attribution to American Action Forum.”