In a previous post, I summarized the important new study from Capital Alpha Partners, LLC, which showed that typical “carbon tax swap deals” would be unable to fulfill their multiple objectives of reducing emissions while providing relief to low-income households and pro-growth tax cuts. Using conventional budget-scoring methods for legislative analysis, the Capital Alpha Partners (CAP) study showed that a new carbon tax would only net the government some 32 cents on the dollar.

Marc Hafstead at Resources for the Future (RFF)—an organization that has been supportive of a carbon tax for years—recently published a critique of the CAP study. Unfortunately, Hafstead completely ignored the main purpose of the study, which was to demonstrate that the typical carbon tax proposals would run out of money.

Besides ignoring the major conclusion of the study, Hafstead spends the majority of his critique showing that projected emissions will be lower according to the latest models in the literature. However, as Hafstead implicitly admits, much of the difference—which is only about 6 percent—is simply due to the fact that projections have changed in the two years since the study’s original estimates were developed. Specifically, the gap between Hafstead’s estimates and the CAP study’s are only slightly bigger than the gap between the U.S. government’s 2016 versus 2018 projections.

Finally, Hafstead mischaracterizes the study’s claims about emissions and the Paris climate agreement. Hafstead argues that a reasonable carbon tax could allow the U.S. to hit the Obama-era Paris pledge of 2025, but the CAP study itself acknowledged this. It was rather the long-term 2050 goal that only a draconian carbon tax would achieve, and the CAP study cites the International Energy Agency to back up its claims.

In fairness, I think I understand why Hafstead may have misunderstood some of the scenario descriptions in the CAP study. In this post I’ll remove any possible confusion and show why Hafstead’s critique misses the mark. And to repeat, Hafstead unfortunately chose to completely ignore the CAP study’s main takeaway—that a carbon tax “deal” will run out of money before paying everybody off.

A Difference in Emissions Projections

The only (apparently) serious concern that the RFF critique raises is that Hafstead gets lower emissions projections when he uses the same off-the-shelf model that the CAP study employed. As Hafstead explains:

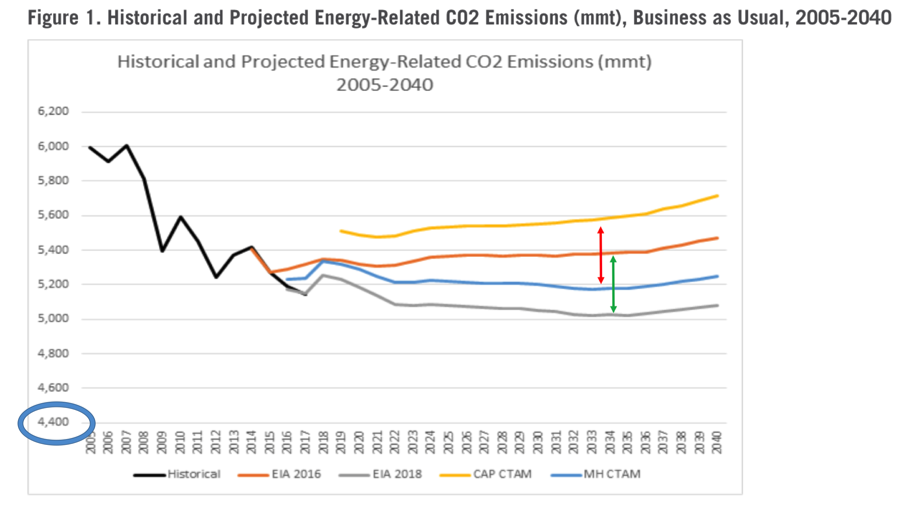

To illustrate the importance of [Washington State’s Carbon Tax Analysis Model] CTAM model assumptions and options, I downloaded and edited the CTAM model myself. Whereas the CAP report uses [U.S. government Annual Energy Outlook] AEO 2016 energy consumption forecasts, I used AEO 2018 forecasts…I also used CTAM default parameter values unless otherwise noted. Figure 1 reports historical and projected energy-related carbon dioxide emissions under business-as-usual from both the CAP results…and my results (labeled MH CTAM). For comparison, I also included AEO 2016 and 2018 emissions projections.

In the figure below, I reproduce Hafstead’s Figure 1, but I have also added two arrows (red and green) and the blue oval, to aid the reader in my commentary on Hafstead’s figure:

In the figure above, the yellow line—labeled “CAP CTAM” in the legend at the bottom—refers to the energy-related carbon dioxide emissions projected in the CAP study. Hafstead’s own projections, derived from the same Washington State CTAM model with the default parameters, are depicted in the blue line. (“MH” presumably stands for “Marc Hafstead.”)

There is a gap between the CAP projections and Hafstead’s projections, to be sure. But I have two points to make.

First, the gap seems larger in absolute terms than it really is, because of the y-axis. As I’ve indicated with the blue oval, the axis starts at 4,400 million metric tons (mmt), rather than 0 mmt which generally speaking is how you should plot data to give the reader a sense of magnitudes. For example, when Hafstead goes on to exclaim, “Most compellingly, there is a significant difference in benchmark emissions between the CAP projections and my own projections—over 300 million metric tons in 2025,” that sounds enormous, but in reality it actually only works out to about a 6 percent difference. This is because Hafstead himself projects emissions at more than 5,200 mmt in the year 2025.

Second, and more important, the major driver of the gap is not that the CAP modelers fiddled with the parameter settings—in fact, they tell me they kept them all at their defaults—but rather that they had been working on the various scenarios for some time, and so based all of their energy forecasts on the U.S government’s 2016 consumption projections.

(Incidentally, the CAP authors chose the emission scenario without the so-called Clean Power Plan [CPP] in effect, because one of the main purposes of the CAP study was to evaluate the Climate Leadership Council [CLC] proposal, which involves an initial $40/ton carbon tax coupled with the elimination of all other climate-related regulations, such as the CPP.)

In the diagram above, I’ve used a red arrow to show the gap between the CAP study and Hafstead’s projection, and a green arrow to show the gap between the 2016 and 2018 projections from the U.S. government. By construction, I made the arrows the same height, so that you can see how close the two gaps are in size. No conspiracy occurred here; the generally accepted estimates of future U.S. energy-related emissions are lower now than they were when the scenarios analyzed in the CAP study were being developed.

Clarifying the CAP Discussion of Paris

Hafstead twice claims that the CAP study says the U.S. can only meet the Obama-era Paris pledge with a “very high” carbon tax. Specifically, in his opening paragraph Hafstead writes, “The authors conclude that only very high carbon prices can reduce emissions sufficiently to meet the US Paris targets in 2025,” and later on he concludes, “one of the key takeaways featured in the CAP report—that very large carbon taxes would be required to meet 2025 emissions targets—is a direct result of using an outdated set of forecasts and parameters inconsistent” with the literature.

Here, Hafstead simply misread the report. However, I believe his misunderstanding was an honest one, because of the way one of the carbon tax scenarios was labeled. First I’ll explain what the CAP study actually said, and then I’ll clear up the possible confusion that may have misled Hafstead.

In the CAP study, in the first main paragraph under the heading, “2. Carbon Emissions and the Paris Agreement,” we read:

Our findings in brief are that the carbon taxes we study, if implemented, would be the highest economy-wide carbon taxes in the world. The carbon taxes would effectively reduce U.S. fuel-based emissions by hundreds of millions of tons of CO2 annually within a few years of being enacted, and some eventually by billions of tons per year. Over 22 years, the carbon taxes we study would achieve cumulative reductions in fuel-based emissions of between 10 and 27 billion tons of CO2. Yet no carbon tax we model is consistent with meeting long-term U.S. obligations under the Paris Agreement as a standalone policy. Two scenarios, phased-in taxes of $72 and $108 per ton, are capable of meeting the U.S. minimum INDC for 2025. Other scenarios achieve meaningful reductions but by 2040 are far off the trajectory needed for compliance with the Paris 2050 goal of an 80% reduction in emissions from the 2005 baseline. Thus, none of the carbon taxes we study could possibly replace all other policies needed to reach the Paris targets in a tax-for-regulatory swap. Our findings are consistent with IEA’s determination that even a carbon tax of $190 per ton of CO2 would fall short of meeting the 2050 Paris goal without a full range of appropriate complementary policies. [CAP study, bold added, footnotes removed.]

As the bold sections above indicate, the CAP study:

- Emphasized that a carbon tax could significantly reduce emissions relative to a no-tax baseline,

- Could (in some scenarios) achieve the short-term 2025 U.S. (Obama-era) Paris commitment,

- Yet could not achieve the long-term 2050 Paris commitment, and finally

- Cited the IEA to confirm this conclusion.

Furthermore, on page 20 the CAP study reports: “Both the $72 per ton and the $108 per ton tax reach the 26% reduction goal…on schedule in 2025. The $49 per ton tax scenario reaches 26% reduction attainment during 2026…” (bold added).

In context, the CAP study is telling the reader that even the mid-sized $49/ton carbon tax would only miss the minimum range of the short-term Paris Agreement INDC by one year (i.e., in 2026 rather than 2025). The rhetorical force of the CAP study wasn’t on 2025 so much as the longer-term goals, for which only draconian carbon taxes would be able to hit—and the CAP study quotes several other authoritative sources which all agree on this point.

So if the above shows that the CAP study wasn’t really emphasizing the 2025 Paris goals, but instead was focusing on the failure to hit long-term goals, why did Hafstead get the opposite impression?

My guess is that Hafstead didn’t look at the main text discussion (which I’ve quoted above), but instead relied on the Executive Summary, which said in the third bullet point:

- No carbon tax we model is consistent with meeting long-term U.S. obligations under the Paris Agreement as a standalone policy. Two scenarios, phased-in taxes of $72 and $108 per ton, are capable of meeting the U.S. minimum Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) for 2025. Other scenarios achieve meaningful reductions, but all are far off the trajectory Paris requires by 2040, a finding which is also consistent with World Bank and IEA estimates. [CAP study, p. 1, bold in original.]

If Hafstead just read the above bullet point, I could understand why he thought it was such a coup for him to show (in his own Figure 2) that the NEMS model shows a carbon tax of just $25/ton being able to achieve the short-term Paris target.

In response, let me mention three items: First, notice the bold statement summarizing the bullet point. The CAP study is emphasizing that no politically feasible carbon tax will meet the long-term Paris pledge. Second, as the last sentence in the bullet point explains, this finding isn’t unique to the CAP study; the World Bank and IEA agree. Third, note that the high carbon taxes discussed in the bullet point are “phased-in,” meaning they are not initially set at those high values. Specifically, the $72 tax is phased in over five years, while the $108 tax is phased in over ten years. (See Table 1.2-1 on page 8 of the report for more details.) This means the apparent gap between Hafstead’s findings and those of the CAP study, isn’t as wide as he may have initially believed.

Even so, Hafstead’s basic point is correct that different models make different assumptions about the “elasticities” involved in the economy’s response to carbon taxes of various sizes. Yet as Hafstead’s own post implicitly confirms, the CAP team took the Washington State model and kept its default parameter settings. Their point wasn’t to come up with idiosyncratic estimates of emission projections. Instead, the whole focus of the CAP study was on revenue projections, for which they used a publicly available, reputable model to generate the scenarios, to which they then applied standard budget scoring protocols.

Conclusion

The new IER-sponsored study from Capital Alpha Partners uses a reputable, publicly available model along with standard budget scoring protocols to conclude that a carbon tax would only raise some 32 cents on the dollar. That was the number-one takeaway from the study.

In his critique, RFF scholar Marc Hafstead completely ignores that crucial message. Instead Hafstead focuses on the fact that his own use of the same model gives emission estimates that are 6 percent lower. However, most of this gap is simply due to changing projections in the time since the CAP scenarios were originally developed. The CAP team used the U.S. government’s own forecasts, which were the latest available at the time the scenarios were being developed for the budget analysis.

Finally, Hafstead accuses the CAP authors of either incompetence or duplicity when they say the U.S. couldn’t meet its Paris obligations with a moderate carbon tax. Yet as I’ve shown, Hafstead simply misread the study, which admitted that three of its studied tax scenarios could hit the short-term Paris target either on time or one year late. What the study stressed was that only very high carbon taxes coupled with other regulations had any hope of hitting the long-term Paris pledge.

All in all, the critique from RFF should bolster the reader’s confidence in the main takeaway from the CAP study, namely that a new carbon tax will not raise enough net revenue to satisfy the promises its backers have made to various groups. I am happy to get into the weeds and discuss the 2025 versus 2050 Paris goals, but the main result—in neon lights—was that the “carbon tax deals” being pushed in certain circles will run out of money. Policymakers and the public should take note that the RFF critique didn’t devote a single word to that headline conclusion.