In the U.S. debate over a federal carbon tax, one of the key arguments is that the receipts from a new carbon tax could be used to reduce other taxes, thereby limiting the damage to the economy. We at IER have warned that this is a very naïve belief, citing historical episodes of “tax swaps” that gave the worst of both worlds, as well as the plans of progressives to use carbon tax revenues to fund “green” projects.

Until recently, the single best trump card in the pro-carbon tax hand was the case of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The BC carbon tax, introduced in 2008, has been called “the best climate policy in the world” by environmental economists. This is because the BC carbon tax was explicitly designed to be “revenue neutral,” meaning that it would only change the composition of taxes, but not the overall level of taxation. In short, the revenue raised from BC’s carbon tax was supposed to offset other taxes, so that the measure would function purely as a way to limit greenhouse gas emissions, rather than acting as a general tax hike.

In this context, a new study from the Canadian Fraser Institute is very important. The authors, Charles Lammam and Taylor Jackson, show that the BC carbon tax was indeed revenue neutral (and then some) early on. But eventually the Canadian government began citing pre-existing tax credits as evidence of the “offset” needed to achieve revenue neutrality. Under an honest accounting, Lammam and Jackson write, “In 2013/14 and 2014/15, the two years for which final data are available, British Columbians bore a combined $377 million net tax increase.”

Thus the single best example of a “carbon tax done right” has collapsed. As was the case with Australia’s carbon tax episode, British Columbia’s carbon tax resulted in a net tax hike. American proponents of a carbon tax should stop assuring conservatives and libertarians that a “deal” is possible that will keep government revenues constant.

The British Columbia Experience

In their Fraser study, Lammam and Taylor explain the original design of the explicitly revenue neutral BC carbon tax:

When the BC government first introduced its carbon tax in July 2008, it was levied at $10 per tonne. This gradually increased to $30 per tonne by July 2012, when it was fully….In its first fiscal year of implementation, the carbon tax generated $306 million in revenue for the BC government…To maintain its promise of revenue neutrality, the government concurrently enacted four new offsetting tax reductions, totalling $313 million, including cuts to personal and business income tax rates, and a refundable tax credit for low income British Columbians. Specifically, the initial offsetting tax measures for 2008 included: a two percent reduction in the bottom two personal income tax (PIT) rates; a reduction in the general corporate income tax (CIT) rate from 12 percent to 11 percent; a reduction in the small business CIT rate from 4.5 percent to 3.5 percent; and the introduction of the low income climate action refundable tax credit (valued at $100 per adult and $30 per child). In its first year of implementation, the carbon tax was revenue neutral, as the offsetting tax measures roughly equaled the value of the new revenue. [Lammam and Taylor, pp. 6-7, footnotes removed.]

However, over time the specific “offsetting tax measures” evolved. To be sure, to this day the BC government officially tells its citizens that the carbon tax has been more than offset by other measures. Yet Lammam and Taylor report:

By 2013/14, it is evident that a major problem has emerged with the way the BC government calculates revenue neutrality: the government no longer relies solely on new tax measures to offset the revenue from the carbon tax. Critically, five of the 16 offsets used in 2013/14 (and an additional offset which was first used in 2014/15) existed in BC’s tax system before their inclusion as tax measures used to offset carbon tax revenue. Put simply, at this point, several of the reported offsetting tax measures are not actually new tax cuts, but are existing tax measures included in the calculation to give the appearance of revenue neutrality….The inclusion of pre-existing tax measures in the revenue neutrality calculation clearly contradicts the government’s original commitment.

Lammam and Taylor then re-work the tax calculations, taking out the clearly pre-existing measures that cannot be included as part of the carbon tax offset. They find:

Once the pre-existing tax measures are removed, the carbon tax ceased to be revenue neutral in 2013/14. In fact, the carbon tax became a net tax increase of $226 million for British Columbians in 2013/14. Neither was the carbon tax revenue neutral in 2014/15 (with a net tax increase of $151 million), the last year of available historical data. In these two years, British Columbians bore a $377 million tax increase.

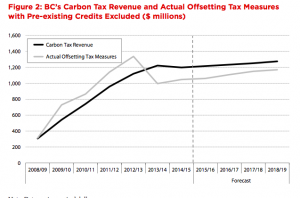

The following figure shows the brief experimentation of actual revenue neutrality, which has now ended.

Source: Figure 2 of Lammam and Taylor (p. 14)

As the figure indicates, the BC carbon tax was genuinely revenue neutral for the first five years of its existence, but in the two most recent years for which we have data, it has represented a net tax hike. Furthermore, the best estimates at the time of the Fraser study’s release indicated that the BC carbon tax would continue to represent a net tax hike for several years into the future.

Conclusion

The hardcore environmental activists who support a large carbon tax (in addition to other measures) do not worry about “revenue neutrality,” and indeed they admitted as much in the failed ballot initiative over a proposed carbon tax in Washington State.

However, a few vocal writers have been urging conservatives and libertarians to cut a deal with progressives on a new carbon tax, assuring them that a “win-win” is possible so long as the new revenues are used for income and/or payroll tax cuts. In this context, the case of British Columbia was important, to show that a revenue-neutral carbon tax was politically possible.

Unfortunately for the pro-carbon tax crowd, the new Fraser Institute study shows that the BC provincial government had to bend the truth as the carbon tax receipts grew. It began counting pre-existing tax measures as part of the “refunds” from the new carbon tax. Thus, the single best example for the pro-carbon tax crowd has collapsed. American conservatives and libertarians should examine any proposed U.S. carbon tax with eyes open.