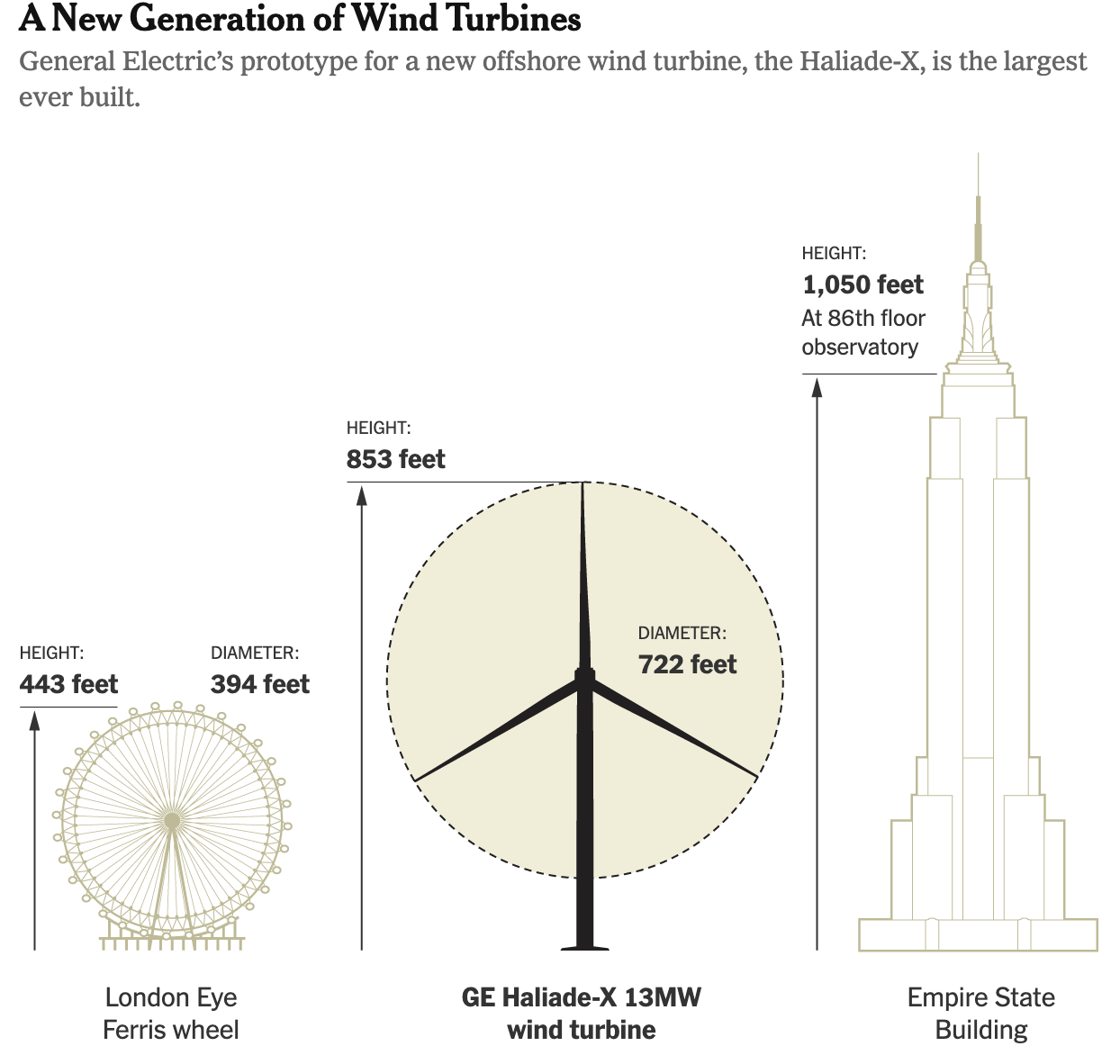

The Netherlands has erected a test model for a new series of giant offshore wind turbines planned by General Electric (GE). The turning diameter of the turbine’s rotor is longer than two American football fields end to end. The test model contains sensors that gather data on wind speeds, electricity output, and stresses on its components. The prototype is the first of a generation of new machines that are about a third more powerful than the largest already in commercial service. A single turbine capacity is about 13 megawatts. Later turbine models are expected to be taller than any building on the mainland of Western Europe. GE expects to eventually deploy at sea, where larger and more numerous turbines are located to capture winds that are stronger and more reliable than those on land. GE’s turbines are currently made in France.

The GE Haliade-X, depicted above, is designed as an offshore wind turbine, to be sited in relatively shallow seawater. Once commercial, the Haliade-X is expected to generate almost 30 times more electricity than the first offshore machines installed off Denmark in 1991.

A larger turbine produces more electricity and, thus, more revenue than a smaller turbine. Size also helps reduce the costs of building and maintaining a wind farm because fewer turbines are required to produce a given amount of power. These qualities that reduce cost are an incentive for developers to use the largest turbines available to increase their ability to win auctions for offshore power supply. However, wind turbines will reach a point where greater size no longer makes economic sense.

GE’s business unit, GE Renewable Energy, is spending around $400 million on design, hiring engineers and retooling factories at Saint-Nazaire and Cherbourg in France. To make a blade of such extreme length that does not buckle from its own weight, GE relied on designers at LM Wind Power, who among their innovations, used a material combining carbon fiber and glass fiber that is lightweight, strong and flexible. LM Wind Power is a blade maker in Denmark that GE bought in 2016 for $1.7 billion.

GE still must figure out how to manufacture large numbers of the machines efficiently, initially at the plants in France and maybe later in Britain and the United States. GE also needs to demonstrate that it can reliably install and maintain big turbines at sea, using specialized ships and dealing with rough weather.

Among GE’s early customers is Ørsted, a Danish company that is the world’s largest developer of offshore wind farms. It has a preliminary agreement to buy about 90 of the Haliade-X machines for a project called Ocean Wind off Atlantic City, New Jersey. On December 1, GE reached a preliminary agreement to provide turbines for Vineyard Wind, a large wind farm off Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts. In order to use GE’s new wind turbines and because it is believed it will be easier to get federal approval under a Biden Administration, Vineyard Wind has withdrawn its construction and operation plans from the federal permitting process. GE also has deals to supply 276 turbines to what may be the world’s largest wind farm at Dogger Bank off Britain. These deals, with accompanying maintenance contracts, could add up to $13 billion.

In the United States, operators of wind turbines get a subsidy to produce electricity (the production tax credit) and offshore wind farms can elect to take an investment tax credit (ITC) that has recently been extended by Congress. The new ITC rules will allow offshore wind projects to retain access to a full 30 percent credit paid by taxpayers for projects that begin construction through 2025. There are an estimated 28.5 gigawatts of offshore wind projects being planned for the U.S. East Coast through 2035, some of which have pushed back completion dates awaiting federal permitting approval.

The Competition

Siemens Gamesa, GE’s key rival, announced a series of competing turbines. It has been easier and cheaper for Siemens Gamesa to build larger turbines than GE because its new models are based off of its existing turbine design template. The company is currently building a prototype for a new and more powerful turbine at its offshore complex at Brande on Denmark’s Jutland peninsula.

Vestas, which until recently had the industry’s biggest turbine, is also expected to unveil a new entry soon.

Offshore turbines now account for only about 5 percent of the generating capacity of the global wind industry. According to the International Energy Agency, capital investment in offshore wind more than tripled over the last decade to $26 billion.

Conclusion

Offshore wind manufacturers are in competition to build bigger and better wind turbines to dot the earth’s coastlines and generate electricity at a lower output level than traditional technologies fueled by coal, nuclear and natural gas because even offshore, the wind does not always blow. The United Kingdom, for example, believes it can power every home with offshore wind by 2030. It is hard to believe that intermittent technology such as offshore wind can do that when electricity storage is still uneconomic. Nonetheless, offshore wind is a booming business currently in Europe, with expectations for Asia with China, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea also building offshore wind farms. GE is contributing to the competition with its Halaide-X wind turbine prototype.