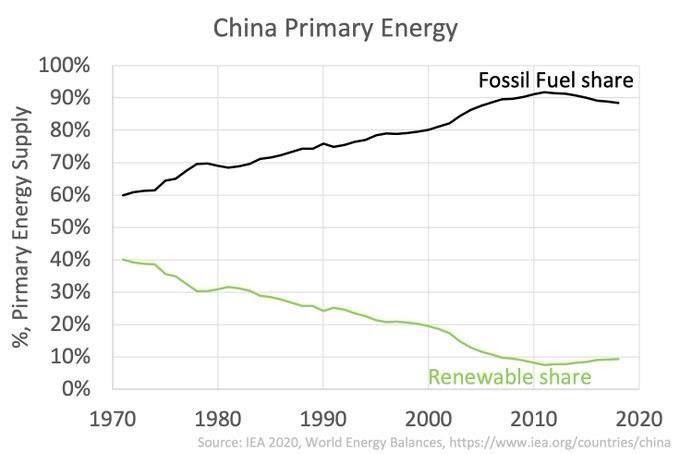

China’s economy is based on fossil fuels (hydrocarbons), which generate 86 percent of its primary energy consumption. China’s investments in these sources continue to grow across the board, despite media characterizations of them as being committed to a “green” energy future. China added 11.4 gigawatts of new coal-fired capacity in the first six months of 2020—plants that can continue operating efficiently for 40 to 60 years. China is allowing coal power plants to be built until around 2030 when China will be richer and replacement technologies will have advanced and their costs will be lower. Chinese state-owned utilities are building new coal-fired power plants, with their fleets set to expand about 10 percent by 2025.

China plans to build 250 gigawatts of coal-fired generating capacity to add to its current coal-fired fleet of over 1,000 gigawatts—more coal-fired capacity than the entire U.S. generating fleet. Last year, China opened the $30 billion Haoji Railway line, a 2,000-kilometer (1,243-mile) conduit to haul 200 million tons of coal a year directly from central coal mining basins to regions in the southeast. Additionally, China is expanding output from its coal mines to supply (at an estimated cost of $90 billion) 35 coal-to-chemicals projects—a technology more carbon-intensive than conventional petrochemical production.

China is also investing heavily in oil-refining capacity and is about to unseat the United States as the world leader in petroleum refining, a position the United States has held for over a century. According to the International Energy Agency, China is expected to dethrone the United States as the number one petroleum product producer as early as next year. One result of the coronavirus pandemic is the loss of U.S. refineries as the demand for petroleum products is reduced due to global lockdowns. Almost 10 percent of U.S. refining capacity is offline due to weak gasoline, diesel and jet fuel demand; plant repurposing; or extended turnarounds. About 1 million barrels per day of U.S. refinery capacity is expected to be idled permanently and about 700 thousand barrels per day are offline for extended work or partial operations.

China is also the world’s largest importers of natural gas. A 2014 deal with Russia’s Gazprom has China importing an average of 1.3 trillion cubic feet of natural gas a year through December 2049 from the newly constructed, 56 inch diameter, 1,875-mile Power of Siberia pipeline. (For comparison, last year Gazprom supplied 2.0 trillion cubic feet of natural gas to Germany through multiple pipelines).

China’s Commitment to the Paris Agreement

According to its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement, China is supposed to peak carbon dioxide emissions around 2030. China therefore has an incentive to increase its greenhouse gas emissions in the current decade to the maximum possible peak. China has also pledged to be carbon neutral by 2060. To meet that pledge, China needs to stop building coal power plants immediately. That goal would require China’s coal fleet to decrease to 680 gigawatts by 2030, a reversal of the coal power plant expansion currently planned. The billions that China has pouring into long-lasting carbon-emitting assets demonstrates the worthlessness of China’s pledges to the NDC.

China’s coal industry believes it can coexist with the 2060 pledge. Five years ago, Chinese companies began upgrading their plants to trap more of the small particulates that generate smog, and to produce more electricity from every ton of coal they burn. Chinese power companies tout that their best coal power plants are on the same environmental level as some natural gas-fired units. Chinese companies also believe that technology breakthroughs in areas such as carbon capture and sequestration (CCS), which traps and stores the greenhouse gases emitted when coal is burned, will help to achieve carbon neutrality. China is running demonstration projects using expensive CCS technology, and its top researchers see it as an alternative to clean-energy storage as a reliable 24/7 power source.

Unlike China, which has pledged to increase carbon dioxide emissions until 2030, the United States has consistently reduced emissions. America’s carbon dioxide emissions dropped 14 percent between 2005 and 2019. In the United States, coal capacity is being retired and natural gas and wind and solar capacity are being built. In 2019, 15.1 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity were retired in the United States, 14.6 gigawatts of solar and wind capacity were added, and 7.9 gigawatts of natural gas-fired capacity came on-line. In contrast, China’s 2019 greenhouse gas emission level was 14 billion metric tons carbon-dioxide equivalent, expanding 420 million tons over 2018 or 3 percent. China accounted for close to 27 percent of the world total and, 74 percent of the 2019 increase.

Conclusion

China is likely to be the only major economy to emerge larger at the end of 2020 than at the beginning of the year, in the wake of COVID-19. Its national target of reaching net-zero emissions by 2060 is not likely to be compatible with another generation of coal-fired power plants that it is building, which can operate efficiently for 40 to 60 years. Nor is it consistent with the growth of their refining industry, which is soon to surpass the United States in size.

When President Xi Jinping announced in September that China would be carbon-neutral by 2060, he gave his coal industry a four-decade transition period to find ways to coexist with the pledge or for the rest of the world to realize that decarbonizing makes little sense. But, China’s strategy of decarbonizing the rest of the world through the Paris Accord makes China’s economy even stronger by reducing the cost of the fossil fuels that it purchases and weakens its rivals’ economies. Clearly, China is using global warming to advance its economic, national security and geopolitical interests.